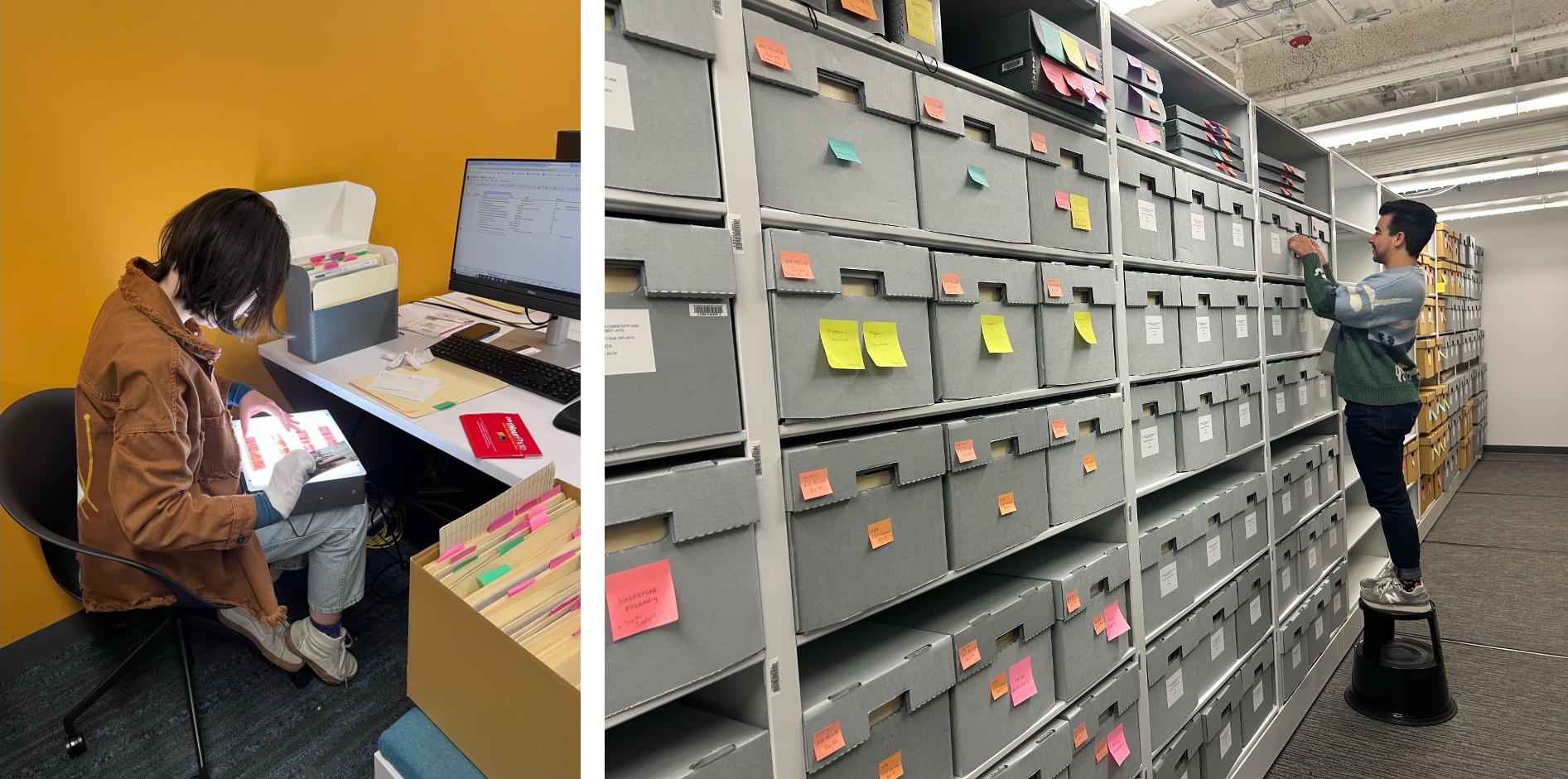

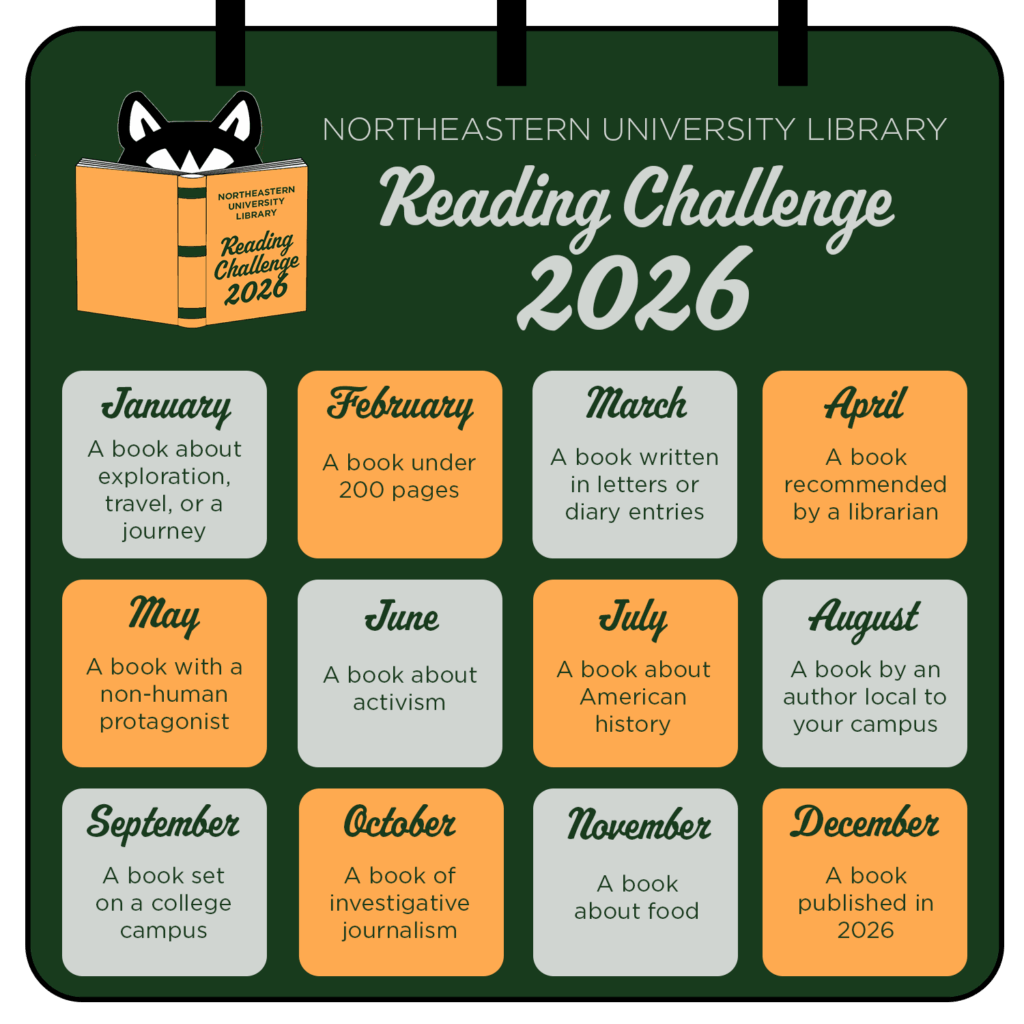

Can you believe it’s already February? The first month of the 2026 Reading Challenge flew by. Speaking of flying, in January, we challenged you to read a book about exploration, travel, or a journey. Congratulations to Avni Sangai, the first winner of 2026, who takes home a Northeastern travel mug to accompany them on all their adventures!

And congratulations to everyone who read a book and told us about it this month. Check out some highlighted reads below. (Reader comments may have been edited for length or clarity.)

What You Read in January

The Mystery of the Blue Train, Agatha Christie

The Mystery of the Blue Train, Agatha Christie

Read the e-book | Listen to the audiobook

“The Mystery of the Blue Train honestly felt like I was traveling with them. Agatha Christie just throws clues at you like she’s testing your brain on purpose. I kept thinking ‘okay, I solved it now,’ and then boom, totally wrong again. The whole luxury train vibe mixed with murder was actually too good. I finished it and sat there like…what did I even just read? This was wild.” — Sonali

“This story is spot-on with the travel and discovery vibe. It fired up my passion for books that bridge different lives.” — Quoc

The Odyssey, Homer

The Odyssey, Homer

Find it at Snell Library | Find it at F.W. Olin Library

“I first read The Odyssey in high school, and at the time, I mostly experienced it as a classic adventure filled with monsters, gods, and trials. Rereading it for this challenge, I gained a much stronger appreciation for its longing for home. I think being a senior made me realize that I will be embarking on unfamiliar journeys soon. I’m unsure if they are far from home, and if so, when my path will bring me back, and so through this reading, I was able to sort out my anxieties and come full circle to excitement for the potential of these adventures.” — Kajal

Katabasis, R.F. Kuang

Katabasis, R.F. Kuang

Find it at Snell Library | Read the e-book | Listen to the audiobook

“I thoroughly enjoyed this book! It was a literal journey to Hell and back that was fascinating, beautifully written, and hurt my brain (in a good way). I found R.F. Kuang’s portrayal of Hell to be fascinating, although I wished there was slightly more Dante influence in her interpretation. The characters’ exploration of Hell was fun, devastating, weird, and at times, slow…but all around, I loved this book and highly recommend it. Starting off 2026 with a 5-star read!!” — Caroline

“Katabasis is about a grad student who journeys through the various rings of hell to retrieve her advisor. Arguably relatable to many of us.” — Sherwin

Into Thin Air: A Personal Account of the Mt. Everest Disaster, Jon Krakauer

Find it at Snell Library | Find it at F.W. Olin Library

“About the 1996 Everest Disaster (narrated by a guy who survived the ordeal), an absolutely crazy situation that I’m surprised I’d never heard about until this book.” — Quinn

What to Read in February

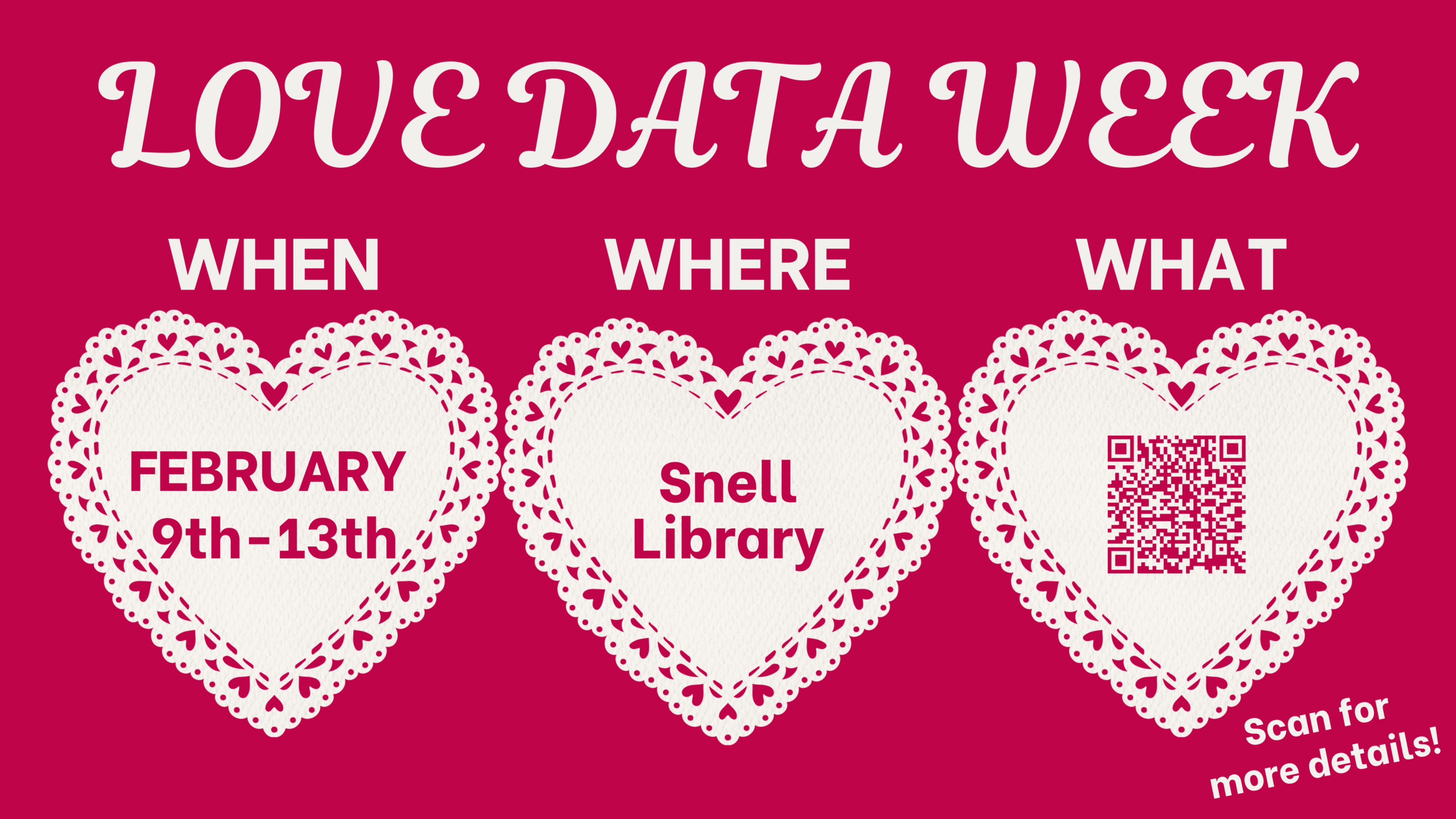

Because February is a short month, we’re challenging you to read a short book. Specifically, try reading a book that is under or around 200 pages. This could be a novella, a book of poetry, an extended essay, or even a comic book. Need ideas? Check out the e-books and audiobooks recommended by your librarians. If you’re on the Boston campus, you can also stop by Snell Library on Feb. 11 and 12 from 1 – 3 p.m. to browse books from the print collection and pick up Reading Challenge swag.

Remember, whatever you read, make sure to tell us about it to enter the prize drawing!

All Systems Red, Martha Wells (144 pages)

All Systems Red, Martha Wells (144 pages)

Find it at Snell Library | Find it at F.W. Olin Library | Read the e-book | Listen to the audiobook

In a corporate-dominated spacefaring future, planetary missions must be approved and supplied by the Company. Exploratory teams are accompanied by Company-supplied security androids, for their own safety. On a distant planet, a team of scientists are conducting surface tests, shadowed by their Company-supplied ‘droid — a self-aware SecUnit that has hacked its own governor module, and refers to itself (though never out loud) as “Murderbot.” Scornful of humans, all it really wants is to be left alone to watch its soap operas. But when a neighboring mission goes dark, it’s up to the scientists and their Murderbot to get to the truth.

My Sister, the Serial Killer, Oyinkan Braithwaite (226 pages)

Find it at Snell Library | Find it at F.W. Olin Library | Listen to the audiobook

Korede is bitter. How could she not be? Her sister, Ayoola, is many things: the favorite child, the beautiful one, possibly sociopathic. And now Ayoola’s third boyfriend in a row is dead. Korede’s practicality is the sisters’ saving grace. She knows the best solutions for cleaning blood and that the trunk of her car is big enough for a body. Not that she gets any credit. Korede has long been in love with a kind, handsome doctor at the hospital where she works. But when he asks Korede for Ayoola’s phone number, she must reckon with what her sister has become and how far she’s willing to go to protect her.

The Summer War, Naomi Novik (144 pages)

The Summer War, Naomi Novik (144 pages)

Listen to the audiobook

Celia discovered her talent for magic on the day her beloved oldest brother, Argent, left home. Furious at him for abandoning her in war-torn land, she lashed out, dooming him to a life without love. While Argent wanders the world, forced to seek only fame and glory instead of the love and belonging he truly desires, Celia attempts to undo the curse she placed on him. Yet even as she grows from a girl to a woman, she cannot find the solution — until she learns the truth about the centuries-old war between her own people and the summerlings, immortal beings who hold a relentless grudge against their mortal neighbors. Now Celia may be able to both undo her eldest brother’s curse and heal the lands so long torn apart by the Summer War.

What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat, Aubrey Gordon (208 pages)

What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat, Aubrey Gordon (208 pages)

Find it at Snell Library | Read the e-book

Anti-fatness is everywhere. In What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat, Aubrey Gordon unearths the cultural attitudes and social systems that have led to people being denied basic needs because they are fat and calls for social justice movements to be inclusive of plus-sized people’s experiences. Unlike memoirs and quasi-self-help books on “body positivity,” Gordon pushes the discussion further toward authentic fat activism. As she argues, “I did not come to body positivity for self-esteem. I came to it for social justice.” Advancing fat justice and changing prejudicial structures and attitudes will require work from all people. What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat is a crucial tool to create a tectonic shift in the way we see, talk about, and treat our bodies, fat and thin alike.

White Holes, Carlo Rovelli (176 pages)

White Holes, Carlo Rovelli (176 pages)

Listen to the audiobook

Let us journey, with physicist Carlo Rovelli, into the heart of the black hole. We slip beyond its horizon and tumble down this crack in the universe. As we plunge, we see geometry fold. Time and space pull and stretch. And finally, at the black hole’s core, space and time dissolve, and a white hole is born. In White Holes, Rovelli traces the ongoing adventure of his own cutting-edge research, investigating whether all black holes could eventually turn into white holes. He shares the fear, uncertainty, and frequent disappointment of exploring hypotheses and unknown worlds, and the delight of chasing new ideas to unexpected conclusions. Guiding us beyond the horizon, he invites us to experience the fever and the disquiet of science — and the strange and startling life of a white hole.