Digital projects involve complex collaborative networks, and they are at their strongest when they draw on the many different kinds of expertise that their participants have to share. At the same time, it can be challenging to draw together all of those different contributions of information, requirements, needs, and ideas in a single place. How do we bridge the differences in technical, cultural, and disciplinary knowledge within these teams, and create shared documentation that can evolve effectively during the project’s full life cycle?

In the past few months, the Digital Scholarship Group has been experimenting with adapting the functional specification—a writing genre that originated in software application and system development—to serve as a tool for project communication. As part of the Northeastern University Library’s recent LibCon event (a departmental sharing of projects and ideas among colleagues), members of the DSG presented a panel session that explored various aspects of this work from different perspectives. This post draws on those presentations to give an overview of the features, challenges, and possibilities of functional specifications in a digital humanities applied research group.

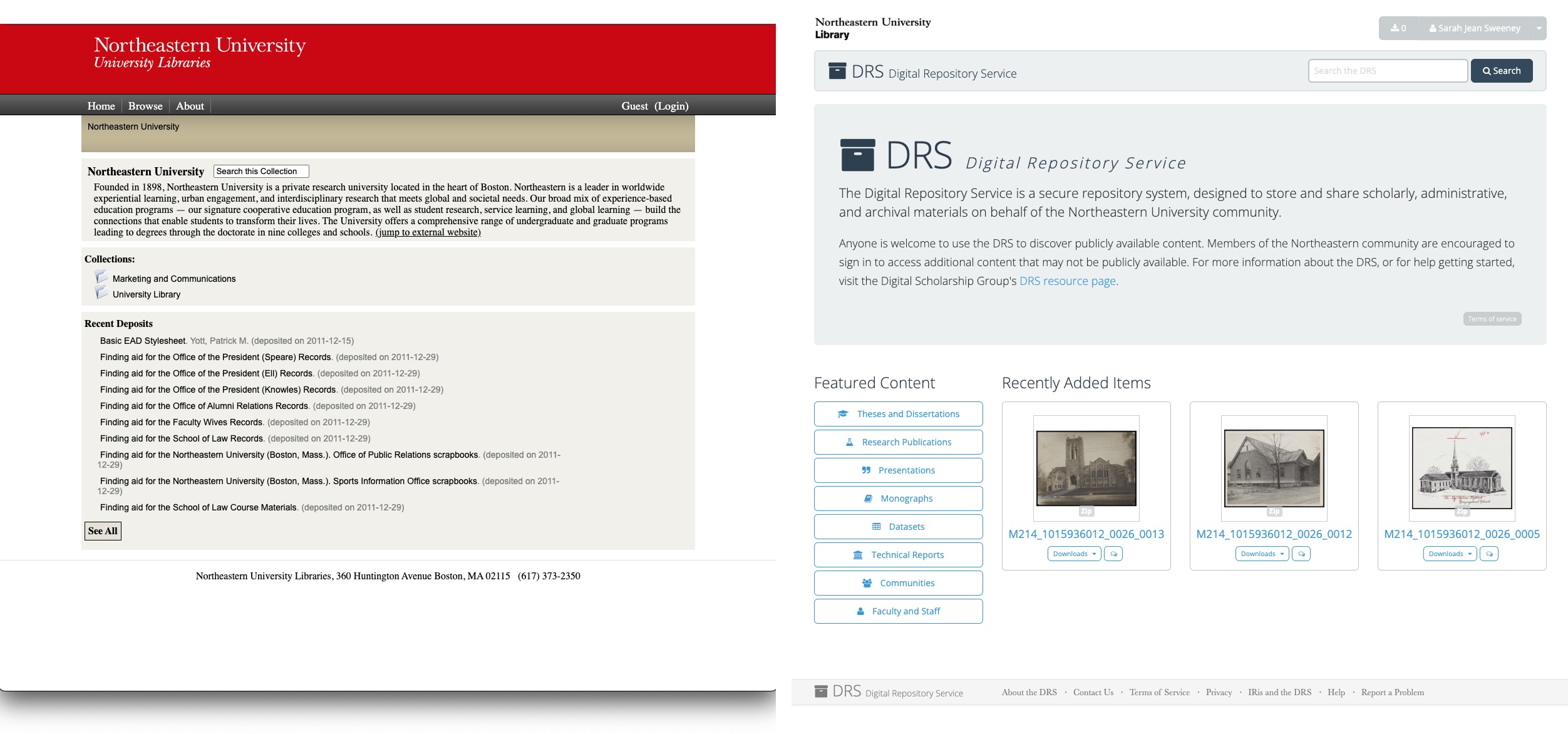

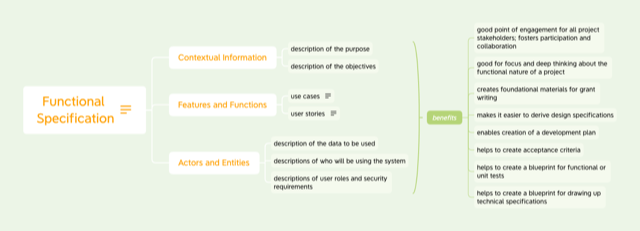

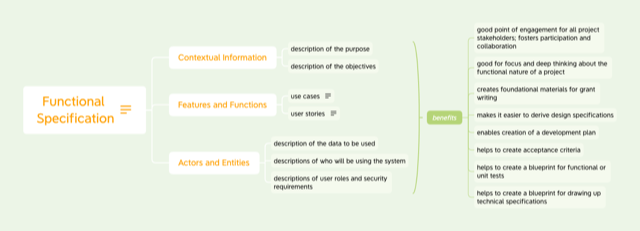

The genre of the “functional specification” in its original context covers several different types of terrain. As Senior DSG Developer Rob Chavez and Associate Director for Systems Patrick Murray-John described it, it captures important contextual information about the purpose and objectives of the project, the features and functions of the tool being developed (from the perspective of specific users and their needs), and the actors and entities (e.g. users, roles, and data) that are involved.

There are numerous benefits from gathering this level of detailed information at the inception of a project. At the level of practical planning, it provides concrete information that in turn makes it easier to develop design specifications, technical specifications, development plans, and tests to determine when a project has been successfully completed: if the functional specification describes a search function that returns results ranked by relevance, we know we’re not done until that is working. Perhaps equally important for the DSG, the process of creating a functional specification fosters participatory collaboration among the project’s constituents and prompts deep thinking about what the project is really seeking to accomplish, and helps the project agree on what it really needs before putting effort into building a working version. It also pulls together information that may be helpful for other purposes (such as grant-writing or publicity).

The functional specification also sits within a wider network of tools. Patrick Murray-John showed how the written document provides detail on specific features (such as searching, or viewing a map, or uploading a new file) which then gets translated into specific programming or design tasks which are stored in project management tools such as an issue tracker. While the functional specification provides a road map, the issue tracker provides a view of progress being made and enables the daily coordination of tasks and effort that are so necessary within a collaborative team. When a given feature is prototyped and eventually completed, the functional specification can then be used again as a confirmation that the real needs of the project have been met, and it can also serve as a place to record unfinished work that may have been out of scope—which in turn might feed into a future phase of the project’s development, or support future fund-raising efforts.

Functional specifications, in their original context in the software development industry, typically operate within a fairly uniform technical team with a lot of shared skills and knowledge. As a result, the common practices and familiar features of this genre mostly focus on its practical and technical aspects: a data inventory, user stories, use cases, preconditions, the logical flow of operations from step to step within a given functional context. For the DSG, experimentation with functional specifications has focused on building out the genre in a few different directions. First, as DSG Director Julia Flanders described through the example of the Digital Archive of American Indian Languages Preservation and Perseverance (DAILP) project, the functional specification can function more effectively as a bridge between different parts of the project team if it includes deeper contextual information: not only user stories, but also detailed information about the motivations and investments of specific user communities, which in turn help the team understand how the project’s data is shaped and why. In the case of the DAILP, understanding the differing needs of language learners, academic researchers, and language experts within the Cherokee tribes is crucial to technical design and decision-making at every level. As the DSG develops templates and guidance for project teams in writing functional specifications, we are putting greater emphasis on those topics and urging projects to use the functional specification as a prompt for early conversation. The DSG has also been experimenting with involving project teams more fully with creating the functional specification itself, rather than treating it as a purely technical genre. DSG Associate Director Amanda Rust discussed her work with the project team for the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project (CRRJ) to develop detailed accounts of the project’s working processes and research, a process that has empowered the group to imagine the functional possibilities more concretely, and intensified their sense of involvement and investment in the development process.

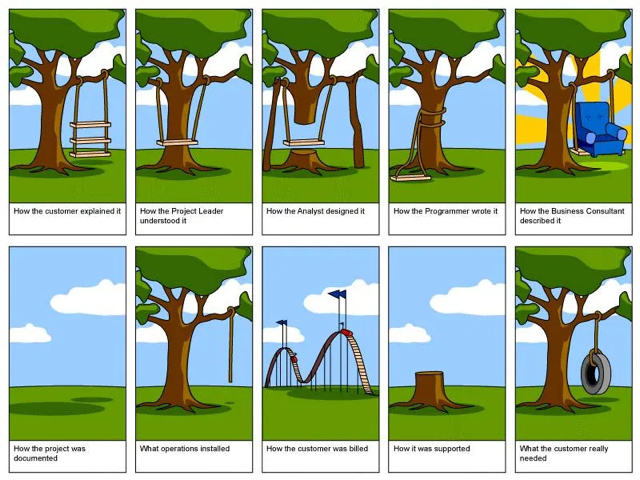

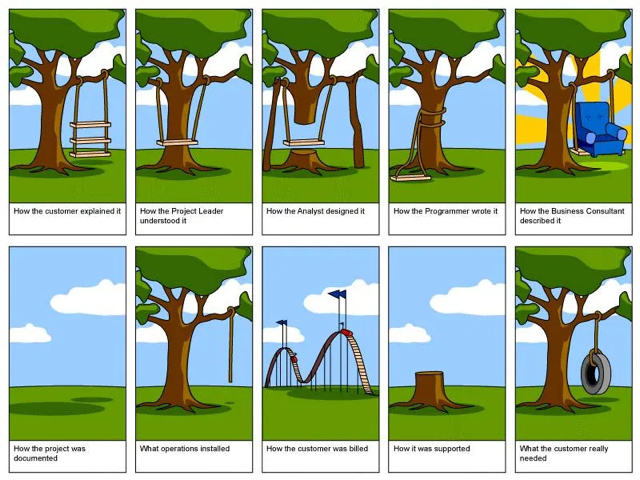

As Senior Digital Library Developer David Cliff pointed out in his contribution to the panel, one of the important roles of the functional specification is to bring clarity and consensus about project scope, and to avoid miscommunication or the dreaded “scope creep” that can occur when functional requirements aren’t clearly laid out at the outset. At the same time, as he and others noted, research projects like these are by their nature prone to change as they explore new possibilities. And similarly the DSG, as an applied research group, is always venturing into unfamiliar territory where precise time estimates are difficult.

The functional specification must therefore tread carefully between attempting to pin things down too closely or prematurely, on the one hand, and leaving things so underspecified that a project is never done, on the other. Iteration plays an important role here: sometimes a project team needs to see a prototype of a search results display before they can imagine the full set of facets and options that will make it truly useful. To be most useful, the functional specification needs to be able to establish achievable interim goals while also keeping track of the project’s largest vision. It is thus always a living and evolving document, and as one audience member pointed out in the panel discussion, it needs to make that evolution possible.

The Digital Scholarship Group has thus far developed three draft functional specifications and a draft template which also documents our emerging practices in this area. In the coming year, there are several areas where further research and experimentation will be needed. First, we want to create a fuller template and more detailed documentation of how and when different parts of the functional specification are most useful, situationally. Second, we want to continue to experiment with involving project teams in the authoring process. Third, we need to develop effective means for translating specific functions from the specification into concrete development tasks (to be tracked via GitHub). And finally, we need to tackle the question of versioning, and create transparent mechanisms for allowing the specification to evolve without losing its documentary value or creating confusion.