Supporting Community Commemoration: 50 Years of the Garrity Decision

Outreach work in archives often intersects with observing anniversaries. This is especially true at Northeastern’s Archives and Special Collections, which houses records of community-based organizations that are still around today. This year, in 2024, community members across the Greater Boston area have been observing the anniversary of the court decision by Judge Arthur Garrity to desegregate Boston’s public schools.

My role as Reference and Outreach Archivist is to connect the community members and organizations with records relevant to their needs in the most meaningful way possible. I do this type of work regularly by providing classes, workshops, and reference and research services. But for occasions such as a 50-year anniversary, reference and outreach work requires customized approaches.

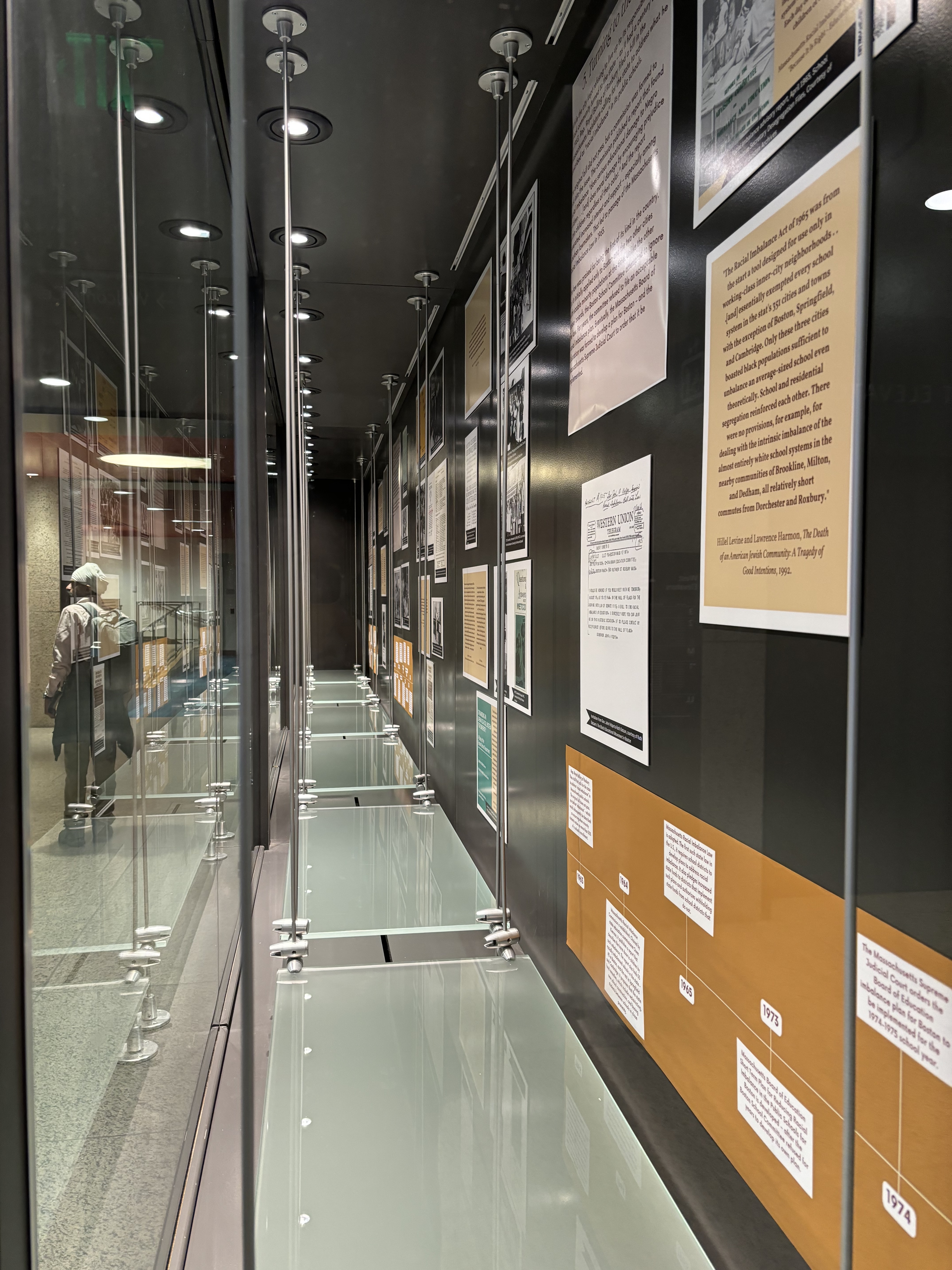

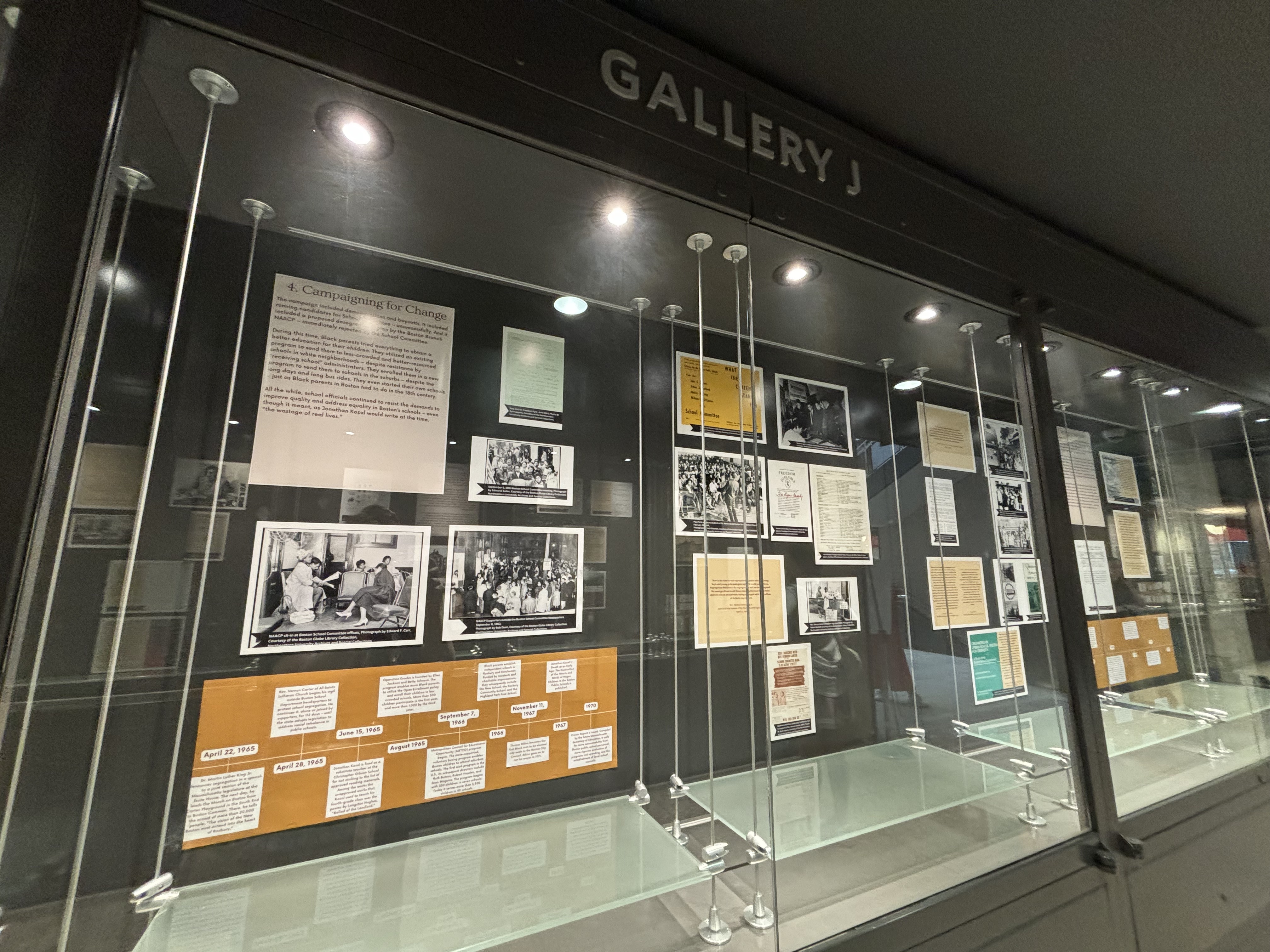

This summer, I managed a very customized approach to archival outreach: coordinating and designing a multi-archive and guest-curated exhibit on school desegregation for installation in the Boston Public Library’s (BPL) Gallery J. While discussion of creating the exhibit began a year ago, when leaders in the Boston Desegregation and Busing Initiative (BDBI helped submit a proposal to the BPL, the curation, exhibition selection, design, and installation happened quickly over the last couple of months. What resulted is a 20-case exhibition in the central branch of Boston’s public library entitled, “A History of Public Education Reform and Desegregation in Boston.”

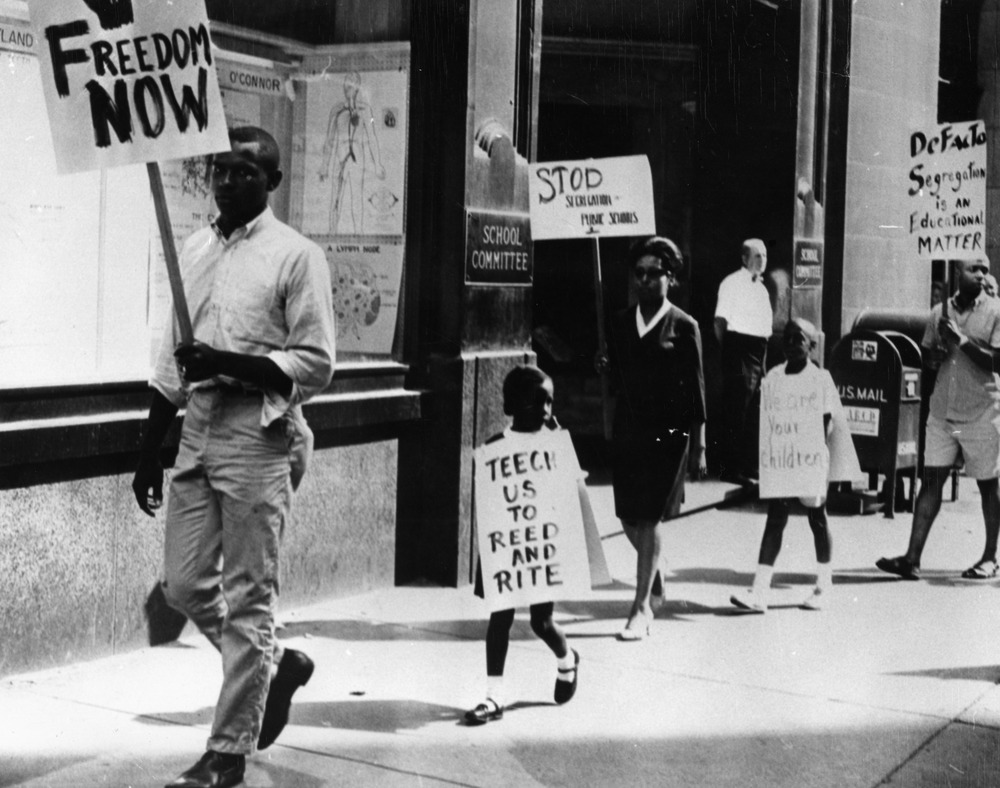

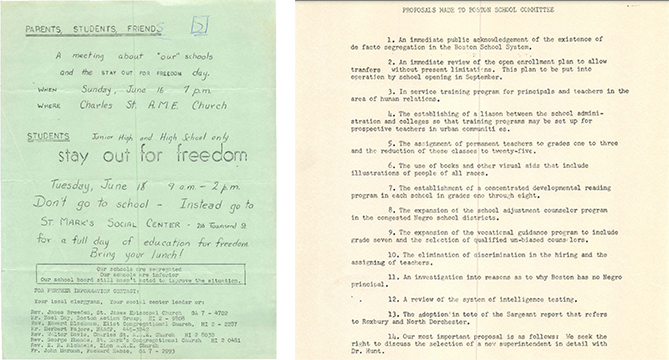

Community historian Jim Vrabel lent his deep knowledge to propose an exhibit observing 10 chapters of Boston’s desegregation history, beginning in 1635 and ending today in 2024. Paired with each chapter was a timeline of events in the long history of education activism and desegregation in the city. Area archives, including the City of Boston Archives, the John Joseph Moakley Archive and Institute at Suffolk University, and the University of Massachusetts Boston Archives & Special Collections in the Joseph P. Healey Library, contributed records that were selected by Vrabel to illustrate the narratives in each chapter. This collaboration resulted more than 90 archival records and excerpts included in the 10 timelines.

After the exhibit narrative had been written and the archival materials selected, it was up to me to design, format, and caption the exhibit, as well as make reproductions to display in the exhibit cases. Northeastern University Library sponsored the printing of the reproductions. All of the exhibit elements were installed for viewing on Sept. 18, in time to serve as a part of BPL’s citywide forums on Sept. 28, offering visual and tangible evidence to the emotional personal stories and responses to the events of school desegregation that still reverberate today.

But not all outreach takes place in an exhibit. Sometimes, a custom outreach project looks like making large-scale reproductions of documents and photographs to spark conversation, kept and stewarded by a partner organization, as I did last September for the BDBI. Other times, it can be providing in-depth rights and permissions labor, approving use of images in projects and suggesting other images to include, as I did for the BDBI and WGBH for their digital walking tour of school desegregation history.

Beyond the digital resources, you can also view the exhibit for yourself by visiting the Boston Public Library’s Central Branch (700 Boylston Street). It will be on display in Gallery J until Jan. 7.

Follow the BDBI for more events and updates, and consider attending their forums at the BPL this Saturday, Sept. 28.