Celebrating Women’s History Month in East Boston

In honor of Women’s History Month, the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections is highlighting the work and accomplishments of two East Boston women: Evelyn Morash and Mary Ellen Welch. Their decades of community organizing and advocacy beginning in the 1960s were effective in improving the quality of life for residents in their neighborhoods, from the establishment of parks and greenspaces to improvements in their neighborhood schools, improved access to healthcare, and mitigation around air and noise pollution from the airport.

Meet Evelyn Morash

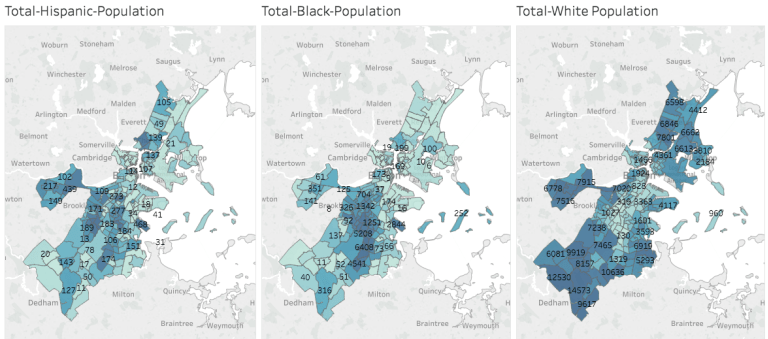

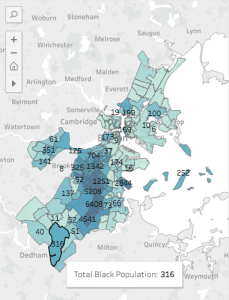

Evelyn Morash grew up in East Boston in the 1930s and ’40s, the daughter of Italian immigrants. As an adult with children in the Boston Public Schools in the 1960s, Evelyn became an outspoken advocate for desegregation and improving education in all the city’s schools. In 1970, she founded the advisory committee Parents and Teachers Who Care, a coalition that grew out of her efforts to ensure school libraries in all of East Boston’s elementary schools. During this same time, Evelyn worked with other community members to establish the East Boston Neighborhood Health Center, which opened in 1970 to serve a geographically isolated and largely immigrant and low-income community. She later served on its board in the 1980s.

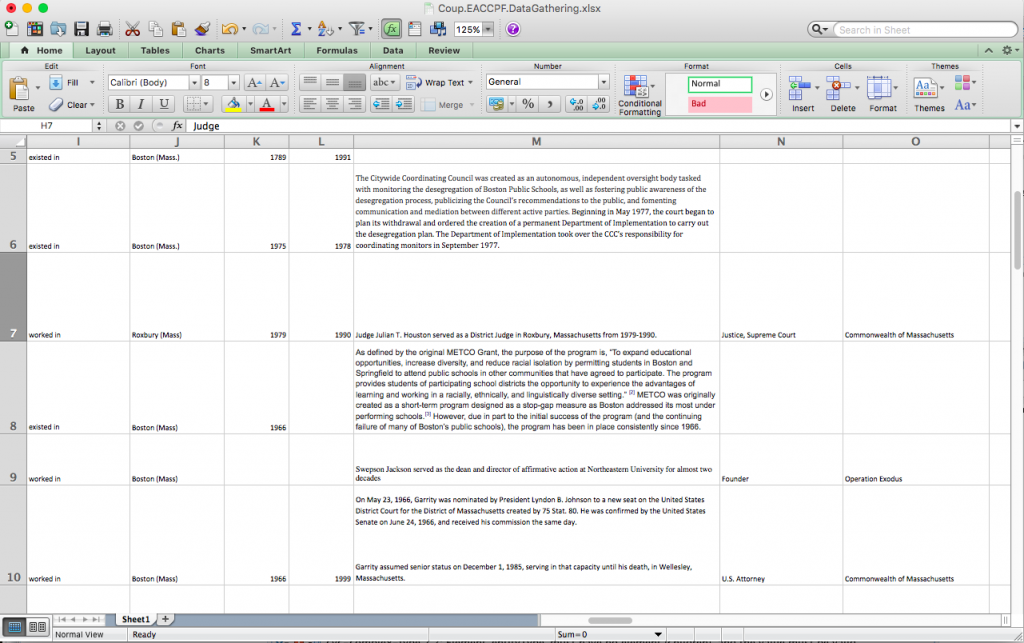

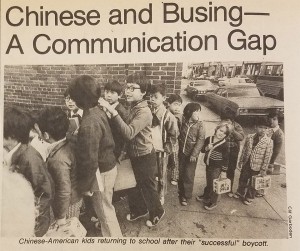

Recognizing her leadership around issues of education in East Boston, Governor Francis Sargent appointed Evelyn to the Massachusetts State Board of Education in 1973, where she prioritized making quality vocational education available for women, since secretarial training was women’s only option at the time. Following the 1974 court order to desegregate Boston’s public schools, Judge Arthur Garrity appointed her to serve on the Citywide Coordinating Council, an autonomous oversight committee to monitor the progress of desegregation efforts across the city. Along with her city- and state-level work, Evelyn continued to focus her activism on East Boston, later serving on the planning committee for the construction of the Mario Umana Academy in the 1980s, where she fought for the new building to serve both as a school and community center for the neighborhood.

The Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections maintains oral histories and written records of Evelyn’s organizing efforts and achievements. In 1997, Evelyn was interviewed as part of the East Boston Greenway Council’s Oral History Project, an effort to capture memories of East Boston from before the expansion of Logan Airport in the 1960s and ’70s and to reflect on changes to the neighborhood. In the recorded conversation with fellow East Boston activist Roberta Marchi, Evelyn describes her early life in East Boston, her involvement with the Girl Scouts, her efforts to establish the East Boston Neighborhood Health Center, and how she got involved in school advocacy. You can listen to both parts of Evelyn’s interview in the Digital Repository Service (DRS) (Part 1 and Part 2).

Two decades later in 2018, Evelyn was interviewed by Greta de Jong about her role in parent organizations during school desegregation in the 1970s and other efforts around school reform. You can listen to the interview and view accompanying materials in the DRS here.

Meet Mary Ellen Welch

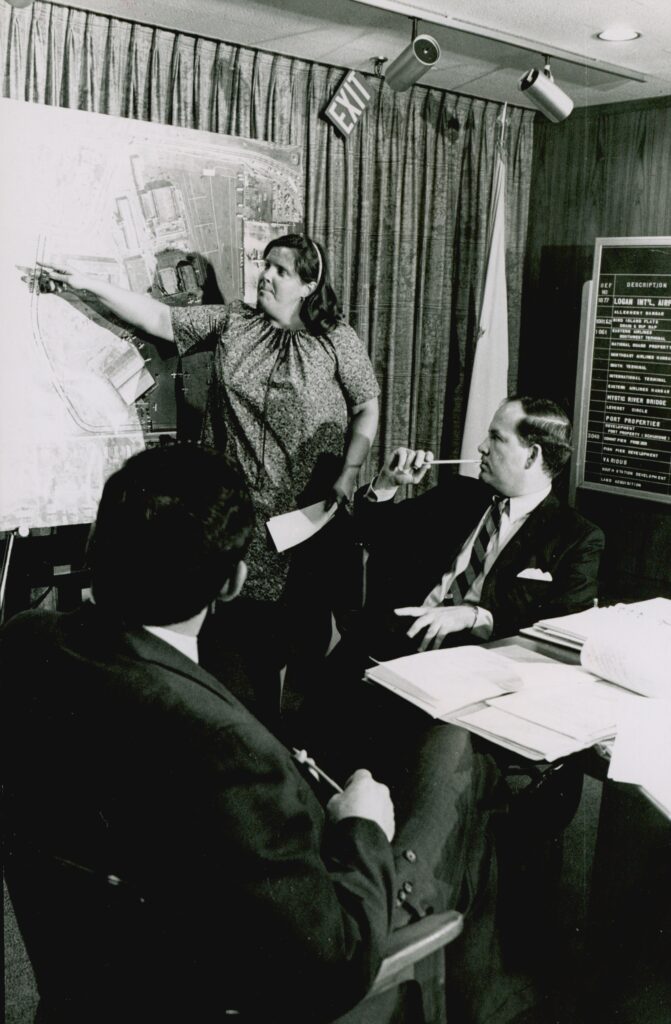

Mary Ellen Welch was an indefatigable activist and teacher at the Hugh R. O’Donnell Elementary School in East Boston, who advocated for civil rights and affordable housing, and against the impacts of airport expansion felt by many East Boston residents, such as noise and air pollution. Throughout her decades of activism, Mary Ellen was active across numerous causes and groups, including the East Boston Neighborhood Council, the East Boston Area Planning Action Council, and Airport Impact Relief.

In the mid-1980s, Mary Ellen, as a member of the East Boston Ecumenical Community Council, joined a newly formed housing committee to address the many issues facing East Boston housing, including absentee owners, rising rents, and lack of aid for the new wave of immigrants from Southeast Asia and Latin America. The committee soon incorporated as its own entity in 1986 under the name NOAH, East Boston’s Neighborhood of Affordable Housing, with Mary Ellen as its first president. Anna DeFronzo, Lucy and William Ferullo, Evelyn Morash, and other prominent East Boston activists participated in establishing the community development corporation.

While the legacy of her neighborhood improvement activism is visible throughout East Boston, it is no better appreciated than along the collection of parks joined by a walking and biking path called the Greenway. In the late 1990s, Mary Ellen helped found the East Boston Greenway Council, a community group that worked with the Boston Natural Areas Fund to identify areas in the neighborhood to transform into recreational greenspace, including the old Conrail railroad yard, now the location of Bremen Street Park. Construction on the East Boston Greenway broke ground in 1997 and opened its first completed section in 2007. Following her death in 2019, the East Boston Greenway was renamed the Mary Ellen Welch Greenway in her honor.

The Mary Ellen Welch papers include personal papers, event flyers, newspaper clippings, reports, letters from O’Donnell Elementary School children to Massport, and other correspondence, the bulk of which relate to Mary Ellen’s anti-airport activism. The collection is available for viewing and research at the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

Further Reading

Evelyn Morash and Mary Ellen Welch participated in a large network of activists and community organizers in East Boston, including Anna DeFronzo, Edith DeAngelis, Roberta Marchi, and the staff at the East Boston Community News. For more archival materials and biographies about these and other East Boston community figures, be sure to check out the following resources:

- Legendary Locals of East Boston (2015) by Dr. Regina Marchi, Northeastern University Library, Northeastern University

- East Boston Community News records (includes digitized issues and a collection fo essays and photographs compiled for its 40th anniversary), Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections

- Boston 200 records, East Boston Oral Histories, Edith DeAngelis (transcript), City of Boston Archives. Learn more about the Boston 200’s neighborhood histories here.