By Julia Lee and Aleks Renerts

Processing assistants Julia Lee and Aleks Renerts recently went through more than 150 boxes of papers belonging to transportation and infrastructure leader Frederick Salvucci. Salvucci’s contributions to infrastructure are numerous: you can become familiar with the scope of his impact by reading his Wikipedia page and listening to his oral history with Head of Archives and Special Collections and University Archivist Giordana Mecagni. The papers he donated to Northeastern encompass his time at MIT, where he has taught since the late 1970s, and document infrastructure projects students were involved in and that he advised on throughout the world.

With the goal of improving access to these records for researchers, Julia and Aleks went through each box carefully, refoldering materials and assigning descriptive keywords. They have selected a few items from the collection to highlight.

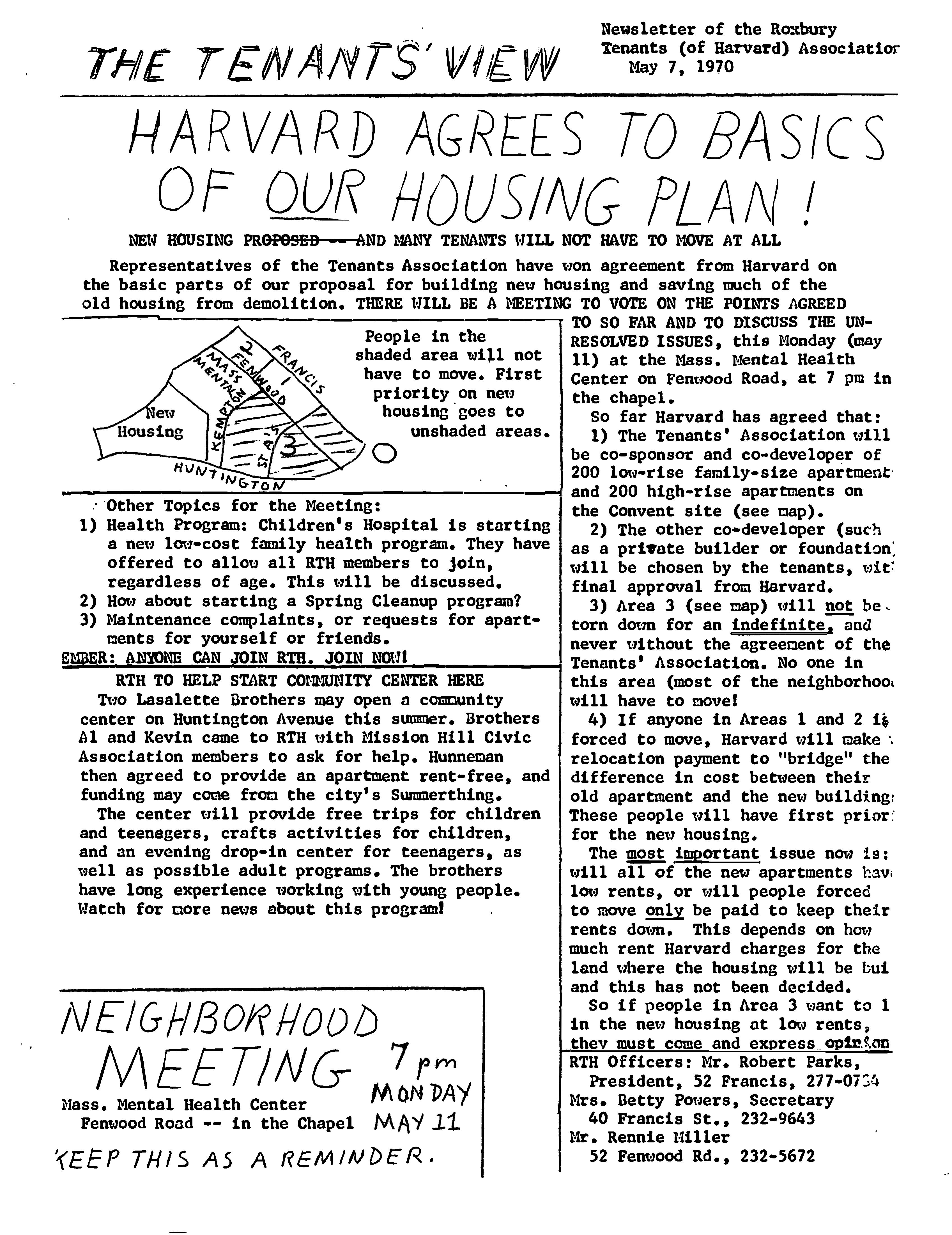

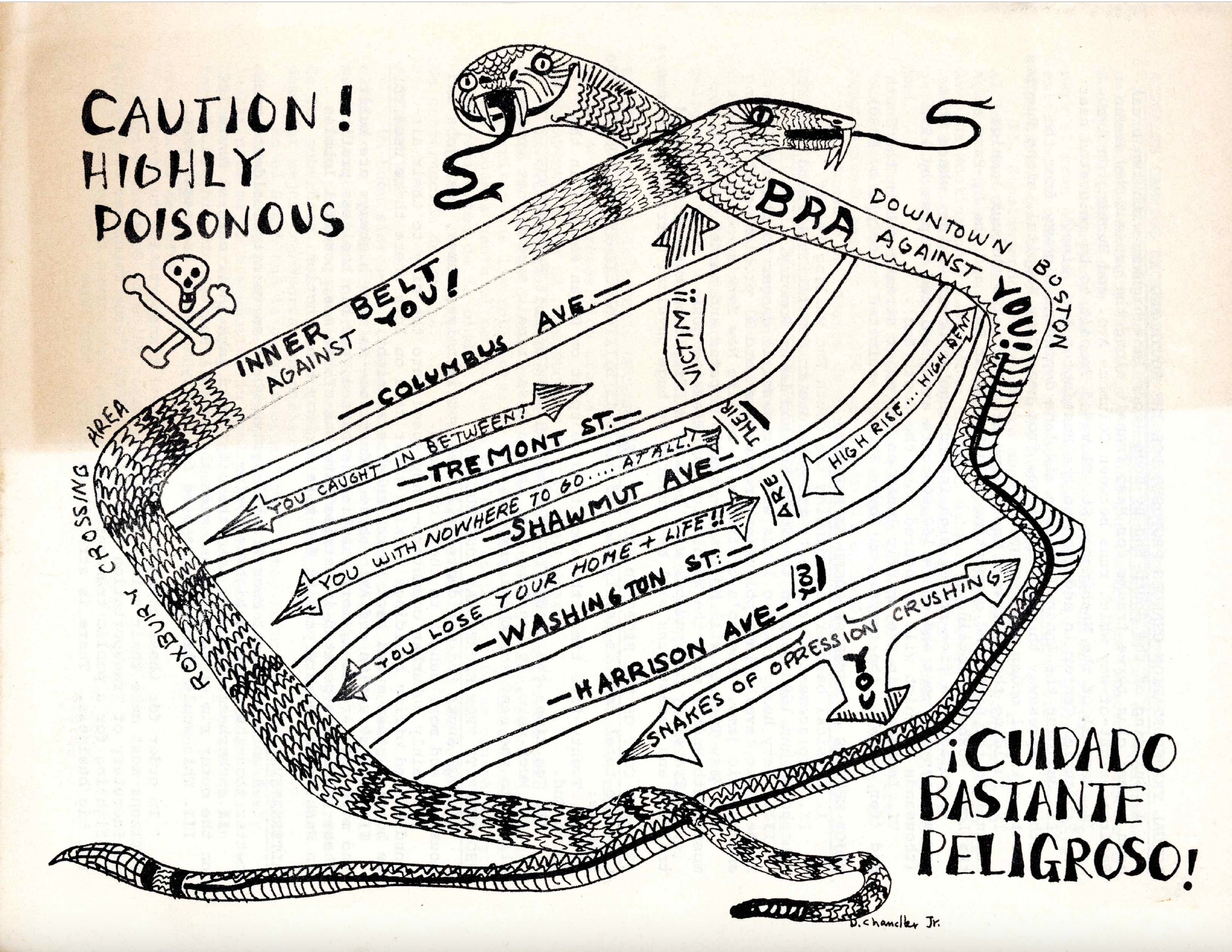

“The Inner Belt” Belt

This commemorative wearable belt is a pun referencing the Inner Belt project. The Inner Belt was a proposed eight-lane highway that would have connected I-93 to I-90 and I-95, stretching from Somerville through Cambridge, across the Boston University Bridge, and through Boston and Roxbury. Plans for the highway would have placed major intersections along its length, disrupting the landscape of many of the neighborhoods of Greater Boston. In the late 1960s and ’70s, construction of the highway was blocked by the actions of a group of city planners, community activists, universities, and politicians, including Salvucci. The defeat of the Inner Belt project marks a significant moment in the history of Boston, transportation in the city, and its history of urban development, as well as setting the tone for Salvucci’s career and focus on the role of community in transportation.

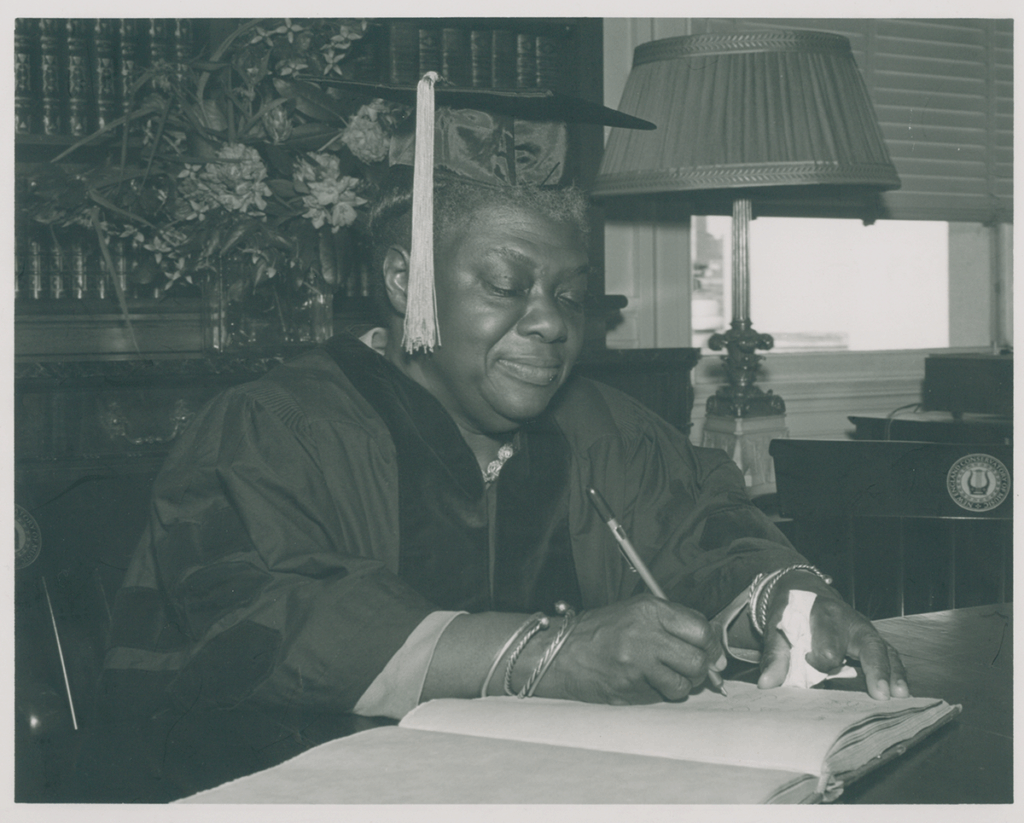

MIT Commencement Exercises

Salvucci taught at MIT as a senior lecturer from 1978-1983 and from 1991 to the present. He has taught courses on transportation and urban planning through the Department of Civil Engineering and worked for MIT’s Center for Transportation Studies (now the MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics). Salvucci’s students were conscious of his impact in the field. Comments on his teaching from the Spring 1991 term repeatedly emphasized his knowledge, experience, and enthusiasm for the material. His ability to give students insight into the “real world” of transportation and civil engineering was praised, and my personal favorite comment creates a delightfully succinct picture of the Salvucci classroom experience: “Great war stories with great analysis.”

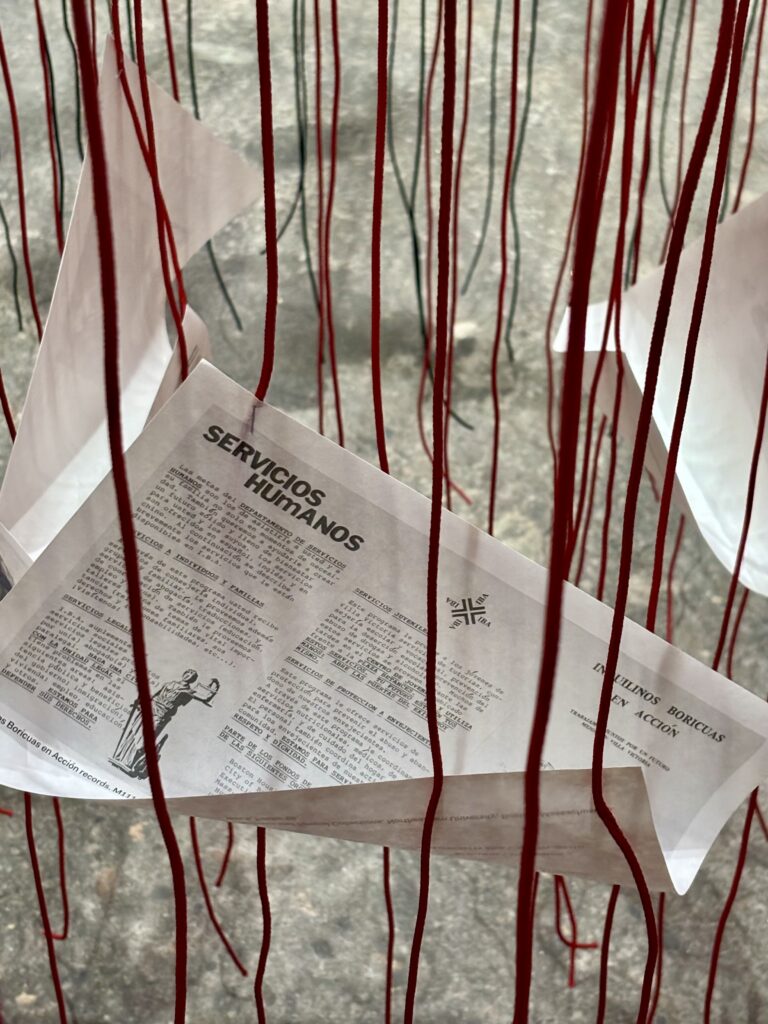

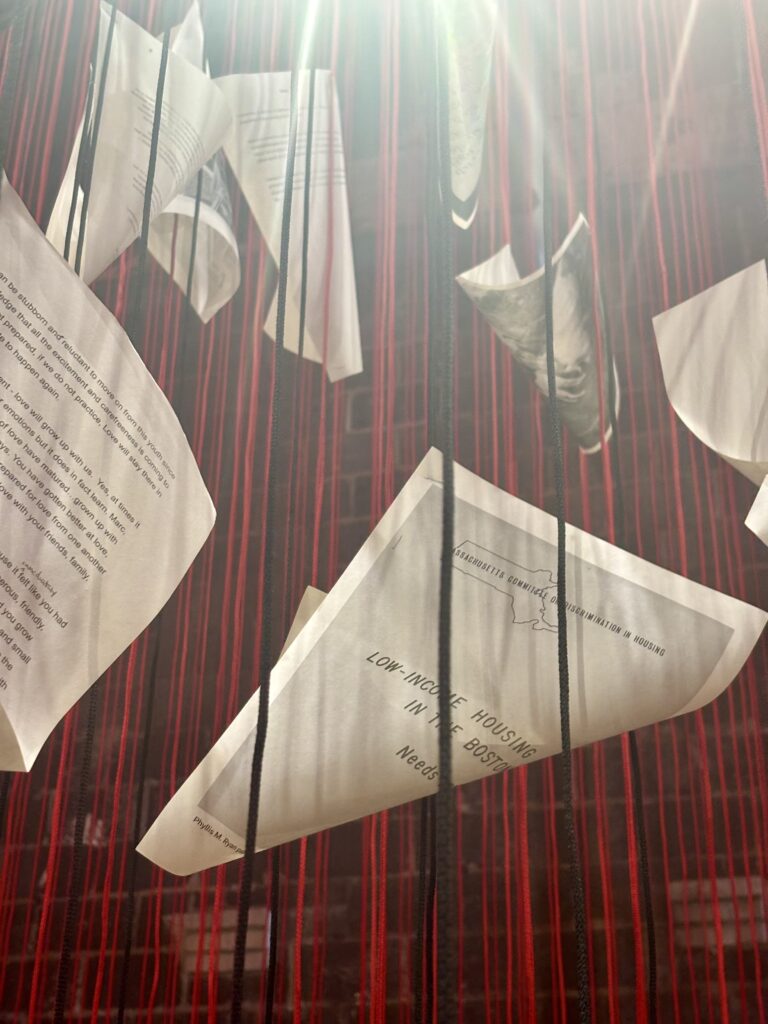

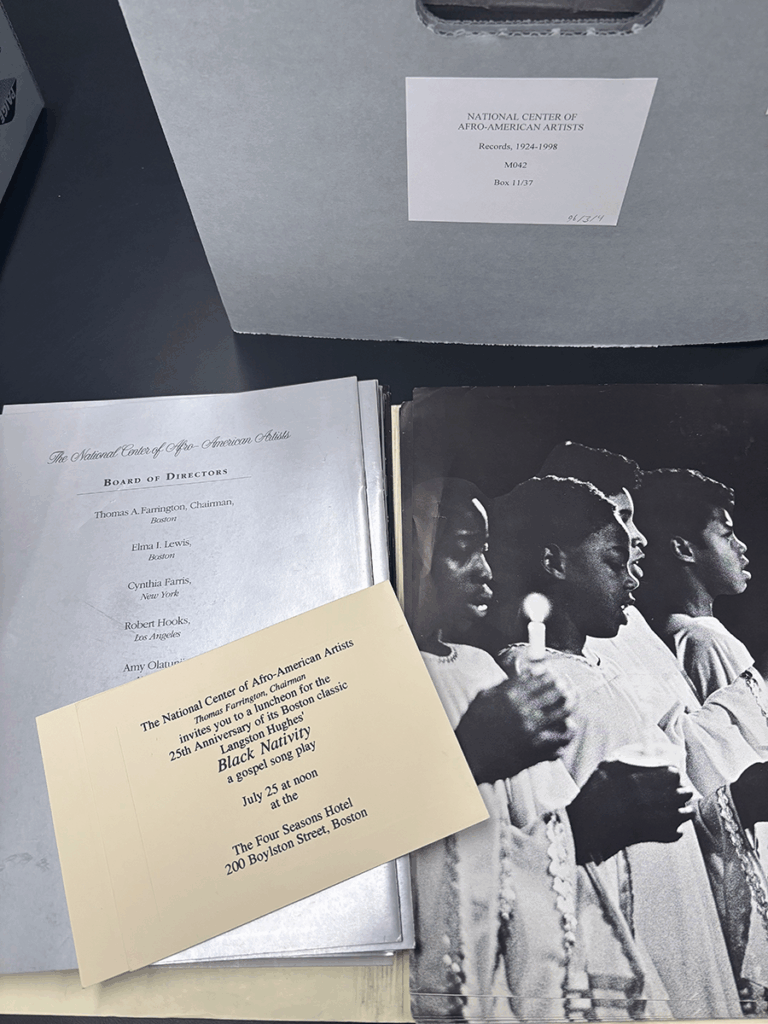

Tren Urbano Encuentro Reports

The MIT/UPR Encuentro Reports represent the nine-year partnership between the MIT Transit Lab, the Puerto Rican Transportation Authority, and the University of Puerto Rico (UPR). From the 1990s to the 2000s, MIT students, overseen by Salvucci, collaborated with students from UPR to “study and advise on the design, operation, and scheduling of the Tren Urbano rail system.” The encuentro (meeting) reports demonstrate the specific concerns and strategies relevant to the Tren Urbano project and showcase student contributions over several years of consultation. This collaborative project formed the model for future partnerships between MIT and various transit authorities around the world, many of which are also well-represented in Salvucci’s work and papers.

Statement of Strategy, London Transport

Boston was not the only city to benefit from Salvucci’s knowledge. Through MIT, he worked with Transport for London (TfL), the government body in charge of most of London’s transportation network, on their Crossrail project. Crossrail, as its name suggests, involved the creation of a new east-west rail line through London with connections to existing major train routes in the UK. Today, it is known as the Elizabeth Line, as Crossrail was the name specific to the construction project. Salvucci’s papers at Northeastern include correspondence and reports from his involvement with TfL that document both Crossrail and the beginnings of London’s Oyster card fare system. I’m personally appreciative of Salvucci’s work in London, as it was the Elizabeth Line that got me to and from Heathrow Airport during a recent trip to the UK.

To learn more about accessing the Frederick Salvucci papers, email the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections at archives@northeastern.edu.

Julia Lee (she/her) is in her first year of the Simmons University Library and Information Science graduate program. She received her BA from Northeastern University with a combined major in English and theatre.

Aleks Renerts (he/him) recently completed a dual MA degree in history and library and information science, with a concentration in archives management, from Simmons University. He received his BA in history from McGill University.