Students of history become familiar with the vast array of human accomplishments. With that knowledge also comes an understanding of human cruelty and racial violence: a perspective humanity shies away from. Perhaps one of the greatest examples of social depravity was in the Jim Crow-era South, a topic I only knew from textbooks and lectures. Working for the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project completely changed my awareness of the subject and opened my eyes to the importance of restorative justice.

The CRRJ (part of the Northeastern University School of Law) spearheads a variety of projects meant to bring justice to the victims of racial crimes. Examples of restorative justice include public apologies, memorials, and reconciliation through education. The efforts of the CRRJ not only provide closure and honorable memory to the families of victims, but also valuable opportunities for law students to advance in their field.

An essential part of the CRRJ’s efforts is the Burnham-Nobles Archive. With an abundance of records (such as police records and death certificates, among many others), the archive serves as the CRRJ’s central hub of information. The latest archive project (set to unveil in 2022) is to transform this data into an interactive and accessible platform that is open to students, researchers, and families. Blending academia, restorative justice, and technology isn’t an easy feat, but it is a relevant and necessary undertaking in today’s society.

I was hired in April of 2021 to work part time assisting the CRRJ’s Burnham-Nobles Archive. I was interested in the position as I recently entered an MA program in Public History and want to work in the archival field. Before working with the project, I was simply passionate about doing archive-related tasks: I didn’t quite realize the breadth of the CRRJ’s project.

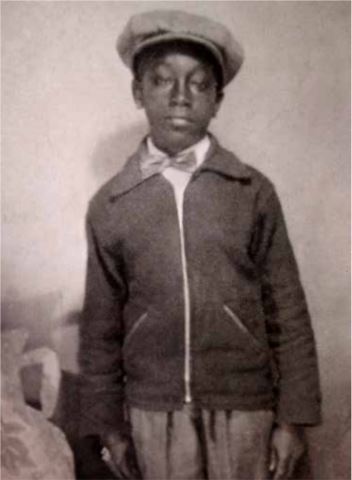

It was not until I started doing actual work that I realized the depths of the horror that was the Jim Crow South. It’s one thing to learn about racial violence, but it’s entirely different to work “face to face” with it. One of my first assigned projects was to code cases from Alabama according to the CRRJ’s v1 data dictionary. This seemed straightforward until I began learning about each victim’s story, their age, and their manner of death. Suddenly, the task had taken on a new level of importance: these weren’t faceless victims of race crimes. They were children, parents, siblings, soldiers, students, and workers—human beings senselessly cut down and unprotected by the law. A tragic example is 14-year-old George Stinney (above), a young boy sent to the electric chair on an unfounded accusation of the murder of two white girls.

Today, my outlook on the project is entirely different, and I have learned so much about the history of racial violence in the South, as well as the important connection between archives, history, and social justice. I have worked on a variety of assignments for the CRRJ, including coding work, GeoNames verifications, case abstract extraction/organization, and work on AirTable.

Working for the CRRJ has been essential for my Public History studies because it has given me the “human” element so often missing from the academic world. While I have learned about racial injustice and violence in the past, working for the CRRJ has allowed me to see each incident on an individual level. Additionally, I feel as if I am actually doing something with my work. Rather than just learning about what happened in the Jim Crow era, I feel that my work is helping the CRRJ accomplish its restorative goals to bring justice to the victims.

The CRRJ and the Burnham-Nobles Archives are leaders in the restorative justice movement, and they have given me valuable experience on both a technical level and a deeply human level.