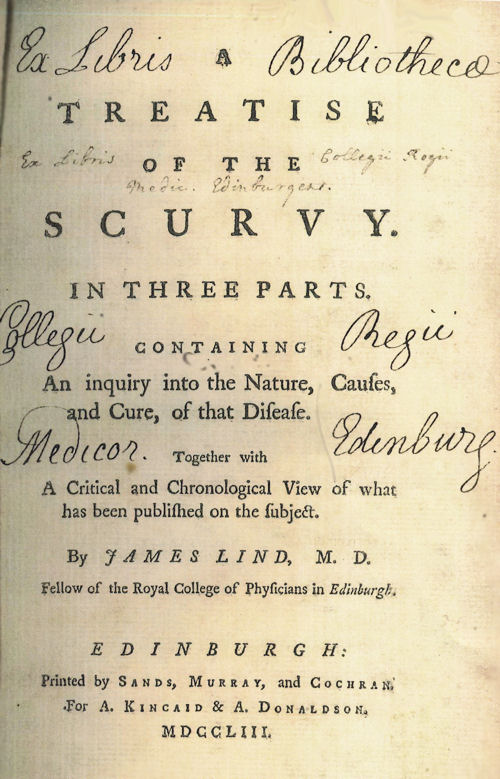

This year is an eventful year in evidence synthesis. Besides marking the launch of the Northeastern University Library’s Evidence Synthesis Service, this year also marks the 270th anniversary of the publication of one of the earliest progenitors of the modern systematic review: James Lind’s A treatise of the scurvy (1753).

James Lind was a Scottish naval surgeon who is frequently credited with conducting the first clinical trial in history, a controlled experiment which evaluated the effectiveness of citrus fruits for preventing scurvy among British sailors. He published the results of this trial in 1753 in the aforementioned treatise.

As was common in 18th century literature, the full title of the publication was significantly more verbose: A treatise of the scurvy. In three parts. Containing an inquiry into the nature, causes and cure, of that disease. Together with a critical and chronological view of what has been published on the subject.

Yes, that’s just the title.

And it’s the final bit of that title–“a critical and chronological view of what has been published on the subject”–which should pique our interest. In providing a comprehensive review and critical evaluation of the published literature on scurvy, Lind essentially conducted an early version of a systematic review.

However, researchers from the 20th and 21st centuries have since pointed out that Lind’s ‘chronological view’ was not truly comprehensive. As Jeremy Hugh Baron of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai wrote in a 2009 paper:

“Lind failed to scrutinize Woodall’s 1617 publication The Surgions Mate with its clear recommendation of equipping ships to the East Indies with lemon juice to prevent scurvy. Nor did Lind cite books by other authors recommending citrus fruits such as Farfan, Hawkins, Clowes, Smith, Ferrari, Moyle, and Esteyneffer, presumably because they were not then in the library of the Edinburgh College.”

Lind missed relevant publications because he relied on only one source: the library at the Edinburgh College. If Lind had searched one of the libraries at the University of Oxford, in addition to Edinburgh College, perhaps he would have found those other relevant texts.

Nowadays we obviously aren’t searching physical libraries when we conduct a systematic review; rather, we’re searching online databases of research articles. And so, you can see a modern parallel in a common mistake made by some systematic review authors: searching only one database. If the authors were conducting a systematic review on a particular nursing-led educational intervention, and the authors only searched the database CINAHL, they may miss out on relevant studies which appear in PubMed, but are not included in CINAHL.

It’s for this reason that those conducting systematic reviews and other forms of evidence synthesis are recommended to search multiple databases. We don’t want to end up like Lind, missing highly relevant material because we failed to search multiple sources.

Unfortunately Lind did not have access to Northeastern University Library’s Evidence Synthesis Service (ESS). But you do! If you are planning to conduct a systematic review or another form of evidence synthesis, we’re here to help. Learn more about the ESS and how we can support your evidence synthesis project here: https://subjectguides.lib.neu.edu/systematicreview

You can read more about the history of systematic reviews here: https://ebm.bmj.com/content/23/4/121

Happy searching!