NU Archives and Special Collections featured in Bill Russell: Legend

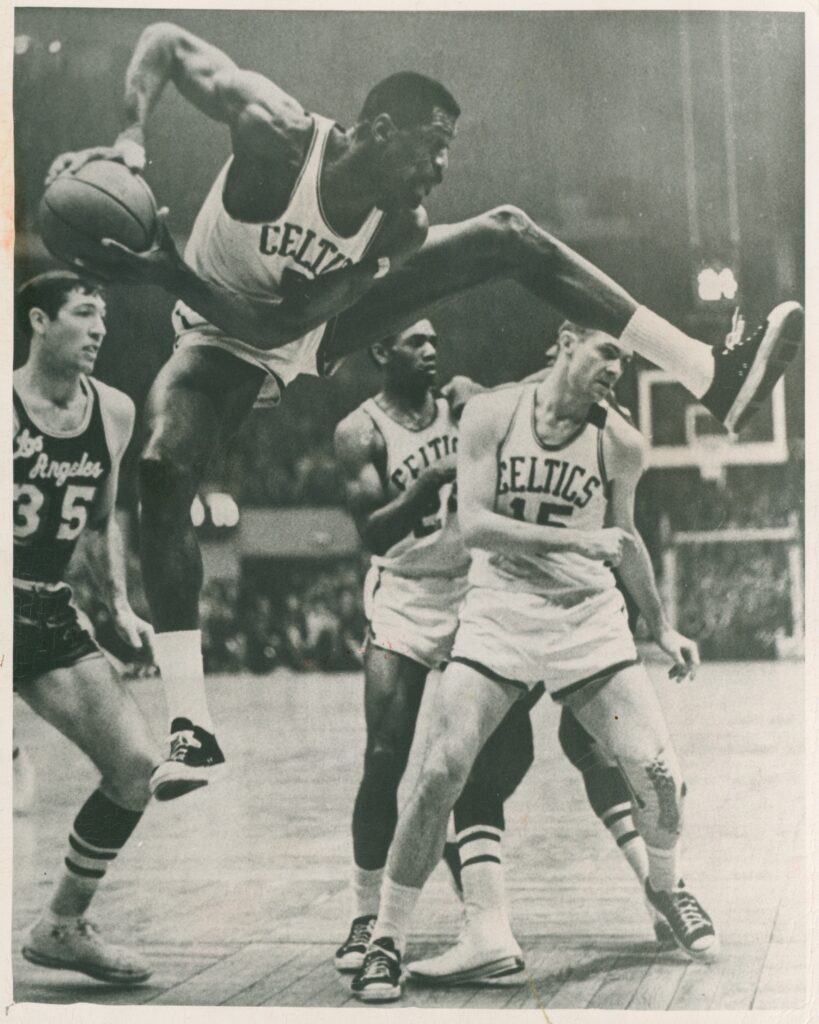

For anyone who has browsed the Boston Globe Library Collection’s sports photographs in the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections, some photos in the Netflix docuseries Bill Russell: Legend might look familiar. The docuseries was released on Netflix February 8 and features many photographs from our Boston Globe Library Collection and also draws upon the Archives’ records of Bill Russell’s social justice history.

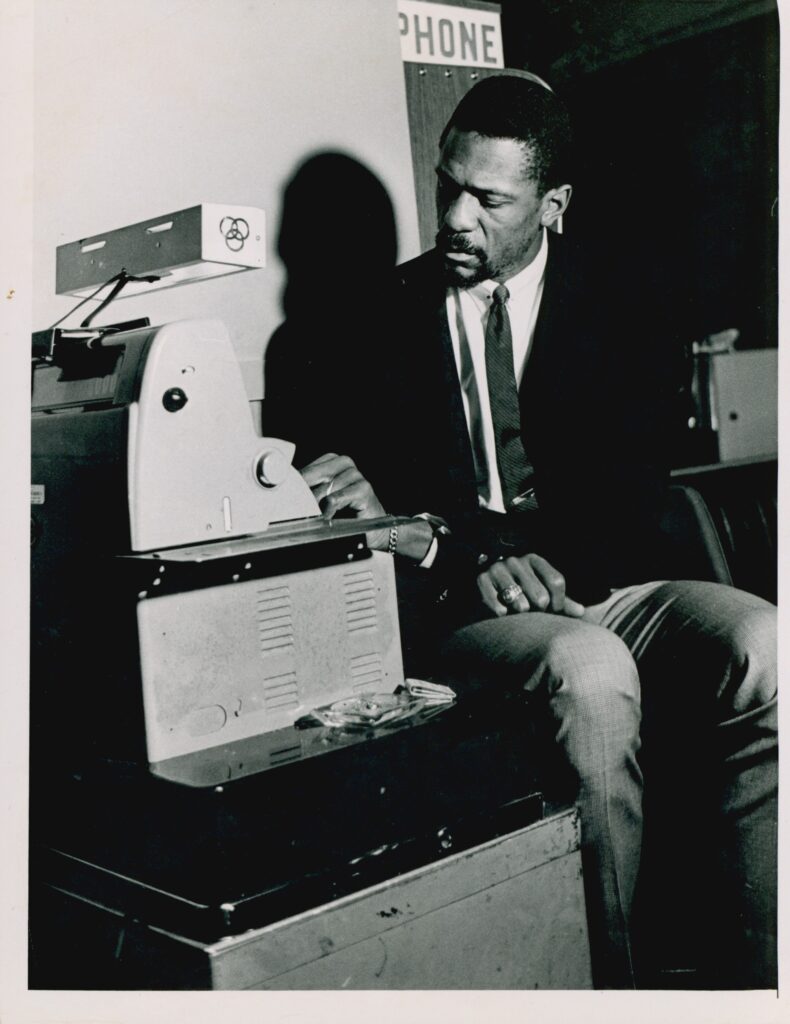

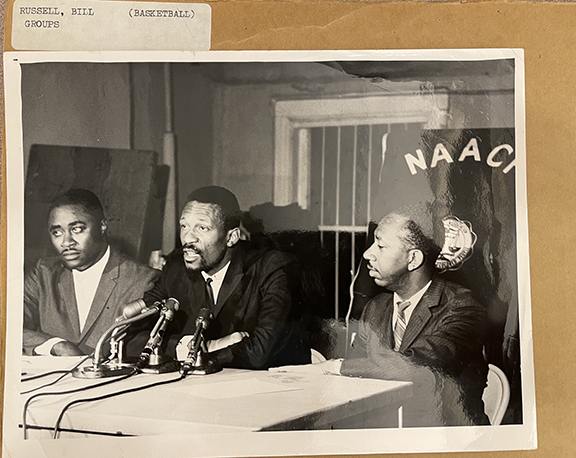

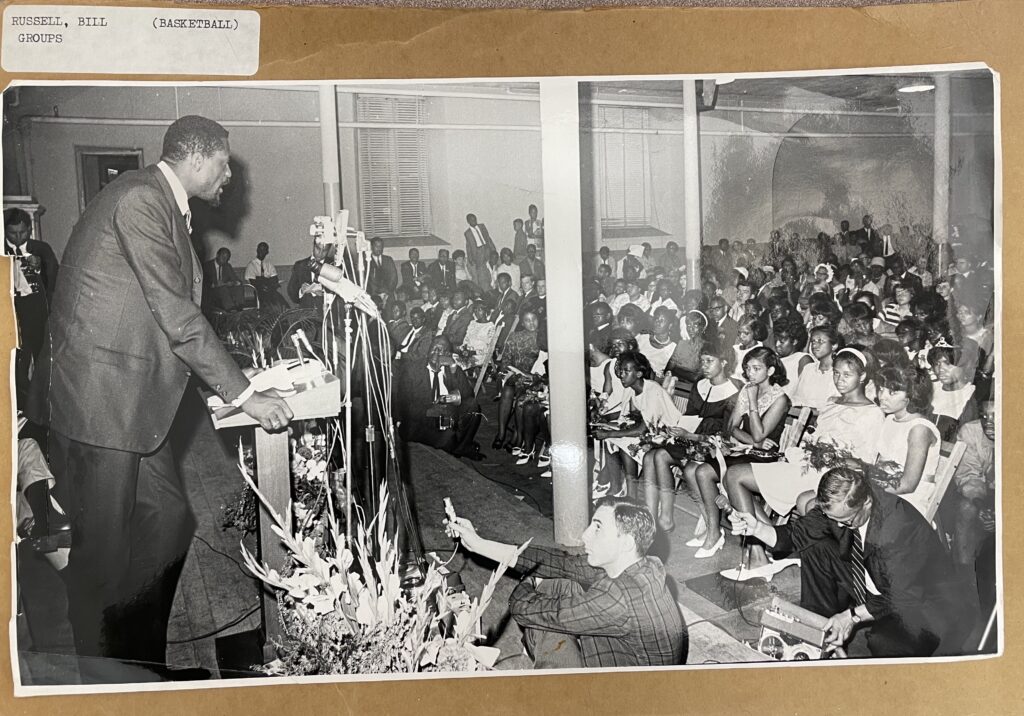

The Netflix docuseries explored many facets of Russell’s life beyond his sports career, which mirrors the records of Bill Russell held in our collection. Along with photographs of Russell coaching and playing basketball, the Boston Globe Library Collection has photos of Russell speaking at school graduations, at press conferences at the Boston NAACP headquarters, at Roxbury neighborhood meetings, and at his restaurant Slade’s Bar and Grill.

Russell is represented in our Special Collections as a frequent presence at Civil Rights demonstrations and Freedom Stay-Outs protesting the racial imbalance in the Boston Public Schools. In an interview, former president of the Boston NAACP branch Kenneth Guscott recalled seeing Russell:

“I remember when we were marching down on one of the marches, there was more than one march, that the star from the Celtics, Bill Russell, he was very active in the civil right movement. When we were marching, Bill was there and he was right in the front line with us, right across. As they marched down Columbus Avenue, this lady came rushing up and said, wait for me, wait for me and she jumped in the line beside Bill Russell. It was his wife. She jumped in that line and started marching with us.”

In a speech by Russell for the Freedom School graduation ceremonies in 1966, he closed by saying asking Roxbury students:

“Is there anyone of you young people here tonight who wants to be President of the United States? Is there anyone who wants to be Secretary of the United States? Would you like to be Ambassador to the United Nations? Why not?

Remember, you can do anything you want to do. If you want to do it badly enough.”

Russell’s legacy is preserved in many archives and special special collections across the country, and many of those archives’ records were gathered to tell the story of Bill Russell’s life in Bill Russell: Legend. Learn more about the Bill Russell: Legend docuseries available through Netflix here.

To learn more about the collection that supplied many images of Bill Russell’s career, visit our Boston Globe Library Collection portal. To learn more about the Freedom Schools demonstrations Russell was a part of visit the Boston School Desegregation Project portal.

You can listen to the full interview with Kenneth Guscott, taken as a part of the Lower Roxbury Black History Project, here.