Katz Tapes Provide Valuable Resource on History of Music Industry

This blog post was written by Sean Plaistowe and edited by Molly Brown and Giordana Mecagni for clarity.

Larry Katz is a music journalist who spent a long career working at Boston-area newspapers and magazines. While collecting information for upcoming articles, it became his practice to record the interviews with musicians and artists and put them aside in case they proved useful in the future. Over time, he amassed a collection of over 1,000 of these interviews, with artists as diverse as Eartha Kitt, Carly Simon, D.J. Fontana (the drummer for Elvis), Aerosmith, David Bowie, Ornette Coleman, Aretha Franklin, Bob Marley, James Brown, Miles Davis, and Elmore Leonard, as well as actors including Ted Danson, Mel Brooks, and Loretta Devine.

In 2020, Larry donated his collection to the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections (NUASC).

These interviews create a fascinating resource that provides insight into the music and arts industry across a wide variety of genres and eras. In them, you can catch some novel and intimate moments of music history. On one tape, you’ll hear Weird Al Yankovic discussing the difficulties of obtaining permission to parody Eminem’s music. Other tapes with artists like Nina Simone or Aimee Mann discuss musical influences or even the challenges and biases of navigating the recording industry. These interviews contain countless quiet moments as well, such as Prince discussing his preference for his home in Minneapolis over either coast, as well as his favorite movies of the year. The quiet clicking of teacups connecting with saucers while Eartha Kitt discusses her career provides a welcome feeling of connection and belonging that can feel rare and precious in researching these figures or music journalism more generally.

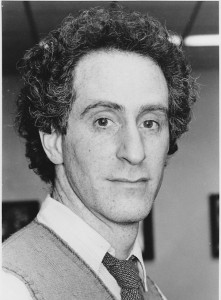

After graduating from the Manhattan School of Music in 1975, Larry Katz worked as a bass player before starting his journalism career at Boston’s Real Paper in 1980. In 1981, Larry worked as a freelance music writer at the Boston Globe and Boston Phoenix before being hired at the Boston Herald as a features writer, where he covered a wide variety of arts and lifestyle beats before settling into a role as a music critic and columnist. In 2006, he became the Herald’s Arts Editor and in 2008, he took over the features department, a role he had until 2011.

In 2013, Larry revisited his tape collection. Re-listening to the interviews sparked memories of the circumstances and contexts that these recordings were made in, information he felt compelled to share. He started a blog, The Katz Tapes, where he began to write reflections on artists and their interviews, often taking into account events that had transpired since the original conversations. Along with these reflections, Larry provided a transcription of the recorded interviews which he often interspersed with links to notable performances or songs related to the artists. Larry also donated the contents of this blog to the NUASC.

Making this collection usable and accessible to the public has involved many hands and collaborations, both internal and external. First, the tapes were digitized by George Blood LP, with funding generously provided by the Library of the Commonwealth program run by the Boston Public Library. Once the digitized tapes were safely back in the hands of the NUASC collections staff, the files were then handed to the Digital Production Services department to do the painstaking work of processing and cataloging the collection. They split audio files that contained multiple interviews, combined interviews that were on multiple tapes edited out white space, and created catalog records.

Making the blog content available was another challenge. Despite already being digital, moving content from Larry’s independent site to Northeastern hosting proved difficult. Initially, I was hopeful that we could use a handy WordPress feature that would allow for the whole cloth export of his blog. No such luck. Instead, I found some scripts which allowed me to scrape the many unique images which Larry had included with each post. The blog also linked to a lot of songs and performances hosted on YouTube, but unfortunately, due to the vagaries of time and copyright law, many of these videos were removed. When possible, I attempted to restore links to sanctioned videos. As an added feature, I created a playlist that includes many of the songs referenced in these posts.

Now that the collection has been cataloged and the blog has been ingested, we welcome anyone to search for their favorite artist, listen to their interview, read some of the reminiscences and insights form Larry about the artist and the interview, and listen to a Spotify playlist of some of the artists Larry interviews at thekatztapes.library.northeastern.edu.

In addition to the Larry Katz collection, researchers and enthusiasts of the arts in Boston may be interested in the Real Paper records and the Boston Phoenix records, both available at the NUASC.