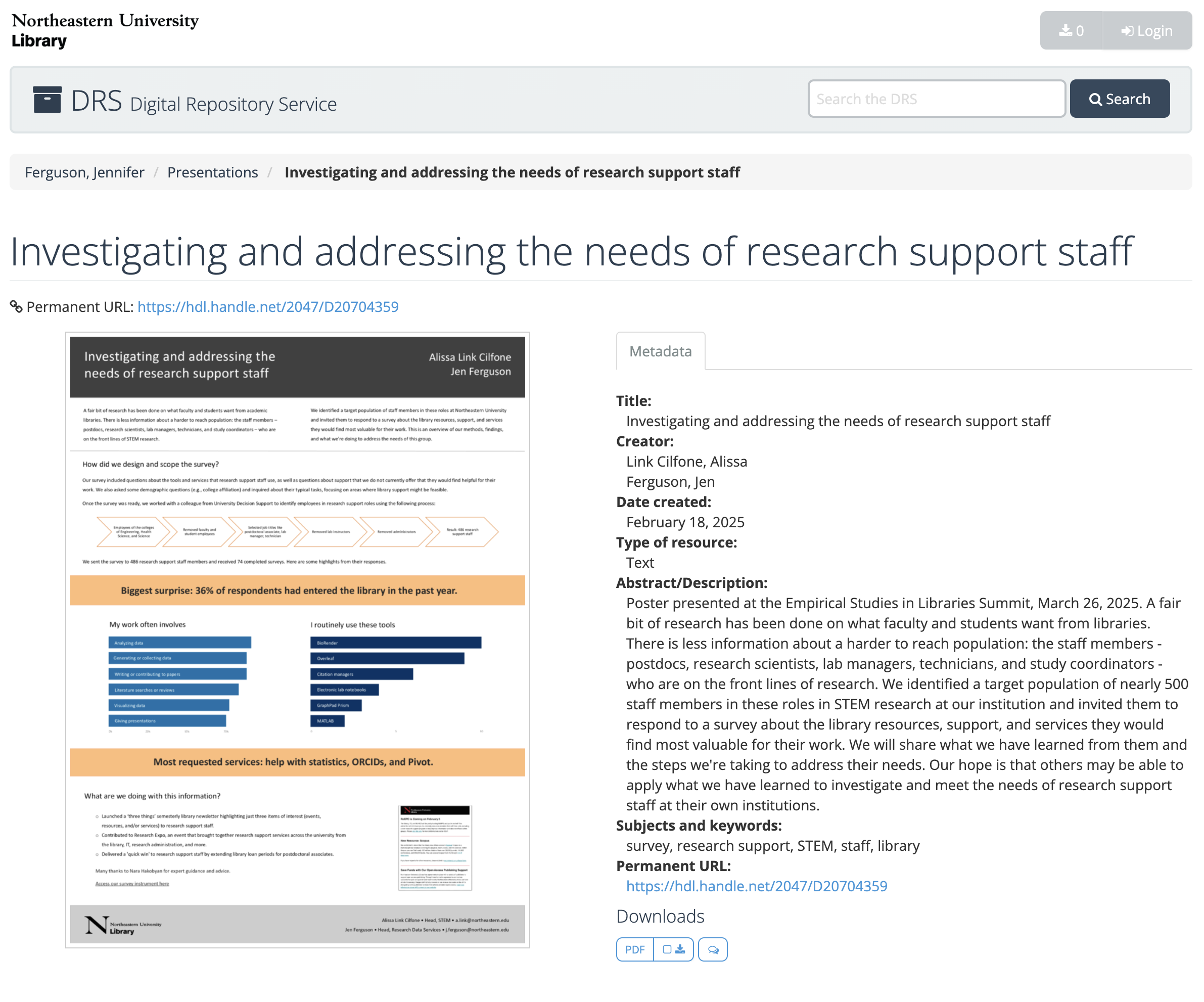

Reading Challenge Update: May Winner and June Preview

The May Reading Challenge winner is Bianca Gallagher! Congratulations to Bianca and to everyone else who read a Reading Challenge book in May.

To be eligible for a prize drawing, make sure to read a book that fits the month’s theme and then tell us about it. In May, we asked you to read a book about your hometown or local area. Here are some of the books you read this month! (Comments may have been edited for length or clarity.)

What You Read in May

Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919, Stephen Puleo

Find it at Snell Library

“Since there are no books about my tiny hometown in Central Mass., I read one about Boston. I have always been fascinated by the Boston molasses flood but didn’t know much about it. This book provided a thoroughly researched account of what led up to the event, the flood itself, and the aftermath as they tried to figure out who was at fault. In a city teeming with history, the flood is often overlooked or joked about but it was tragedy that took place at a pivotal moment of time in Boston and the country.” — Kerri

American Pastoral, Philip Roth

Find it at Snell Library | Find it at F.W. Olin Library

“The New Jersey town name dropping was delightful, and the book was thought-provoking for sure. Wish I’d read an American lit seminar, then maybe I’d understand exactly what he was trying to say about the life and death of the American ideal.” — Jodi

Exciting Times: A Novel, Naoise Dolan

Buy it at Bookshop.org

“Set in Hong Kong, which is my hometown! It’s the first book I ever read set there and it was a lot of fun seeing my childhood spaces represented on the page!” — Nobel

North Woods: A Novel, Daniel Mason

Find it at Snell Library | Read the e-book

“LOVED LOVED LOVED. Reminded me of The Overstory. Made me happy and I wanted to read it. Helped me appreciate and connect with nature. A little technical at times (I had to Google words a lot) but 10/10 recommend.” — Geneva

Suggested Reads for June

In celebration of Pride Month, your June challenge is to read a book that tells a story of resistance. Check out our recommended e-book and audiobook titles in Libby or stop by the Snell Library lobby from 1 – 3 p.m. on June 11 and 12 to browse print books and pick up Reading Challenge swag.

The Other Olympians: Fascism, Queerness, and the Making of Modern Sports, Michael Waters

Find it at F.W. Olin Library | Listen to the audiobook

In December 1935, Zdeněk Koubek, one of the most famous sprinters in European women’s sports, declared he was now living as a man. Around the same time, the celebrated British field athlete Mark Weston, also assigned female at birth, announced that he, too, was a man. Periodicals and radio programs across the world carried the news; both became global celebrities. A few decades later, they were all but forgotten. In The Other Olympians, Michael Waters uncovers, for the first time, the gripping true stories of pioneering trans and intersex athletes. “This riveting audiobook brings all the facts and showcases why we need to acknowledge try history in today’s social climate.” — Book Riot

Book and Dagger: How Scholars and Librarians Became the Unlikely Spies of World War II, Elyse Graham

Listen to the audiobook

At the start of WWII, the U.S. found itself in desperate need of an intelligence agency. The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was quickly formed—and in an effort to fill its ranks with experts, the OSS turned to academia for recruits. Suddenly, literature professors, librarians, and historians were training to perform undercover operations and investigative work—and these surprising spies would go on to profoundly shape both the course of the war and our cultural institutions. Book and Dagger is an inspiring and gripping true story about a group of academics who helped beat the Nazis—a tale that reveals the incredible power of the humanities to change the world.

By the Fire We Carry: The Generations-Long Fight for Justice on Native Land, Rebecca Nagle

Listen to the audiobook

Before 2020, American Indian reservations made up roughly 55 million acres of land in the United States. In the 1830s, Muscogee people were rounded up by the U.S. military at gunpoint and forced to exile halfway across the continent. At the time, they were promised this new land would be theirs for as long as the grass grew and the waters ran. But that promise was not kept. Rebecca Nagle recounts the generations-long fight for tribal land and sovereignty in eastern Oklahoma. By chronicling both the contemporary legal battle and historic acts of Indigenous resistance, By the Fire We Carry stands as a landmark work of American history.

Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson, Tourmaline

Listen to the audiobook

Rumor has it that after Marsha P. Johnson threw the first brick in the 1969 Stonewall Uprising, she picked up a shard of broken mirror to fix her makeup. Marsha, a legendary Black transgender activist, embodied both the beauty and the struggle of the early gay rights movement. She performed with RuPaul and with the internationally renowned drag troupe The Hot Peaches. She was a muse to countless artists, from Andy Warhol to the band Earth, Wind & Fire. And she continues to inspire people today. Marsha didn’t want to be freed; she declared herself free and told the world to catch up.

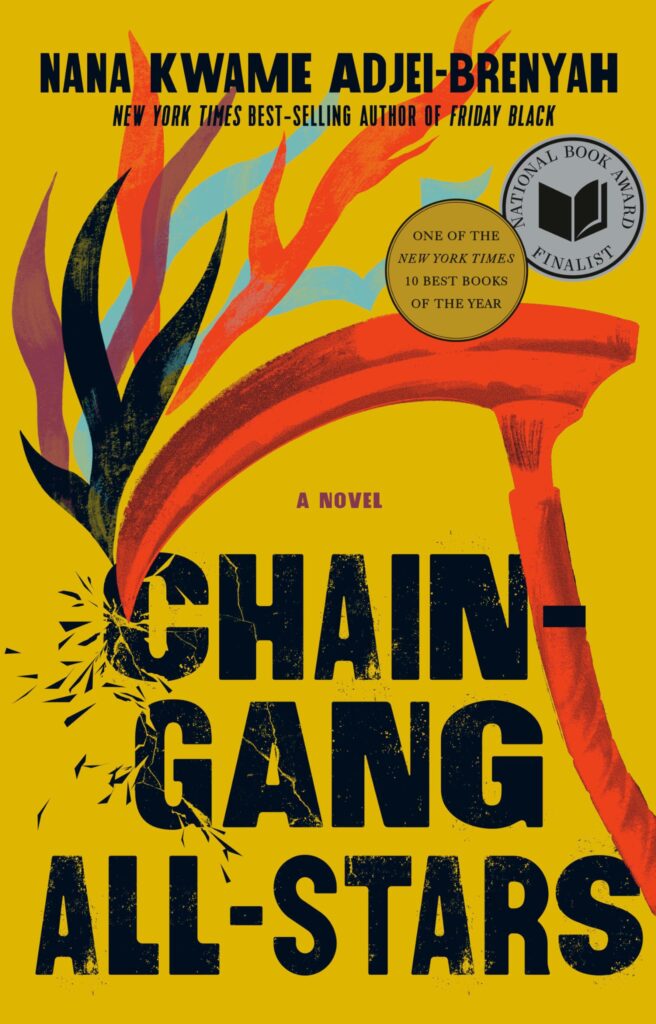

Chain-Gang All-Stars: A Novel, Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

Find it at Snell Library | Find it at F.W. Olin Library | Listen to the audiobook

Loretta Thurwar and Hamara “Hurricane Staxxx” Stacker are the stars of the Chain-Gang All-Stars, the cornerstone of CAPE, or Criminal Action Penal Entertainment, a highly popular, highly controversial profit-raising program in America’s increasingly dominant private prison industry. It’s the return of the gladiators, and prisoners are competing for the ultimate prize: their freedom. But CAPE’s corporate owners will stop at nothing to protect their status quo. Chain-Gang All-Stars is a kaleidoscopic, excoriating look at the American prison system’s unholy alliance of systemic racism, unchecked capitalism, and mass incarceration.

Whatever you read, make sure to tell us about it to enter the June prize drawing. Good luck, and happy reading!