Box By Box: Inside Archival Processing of the Stull & Lee Records

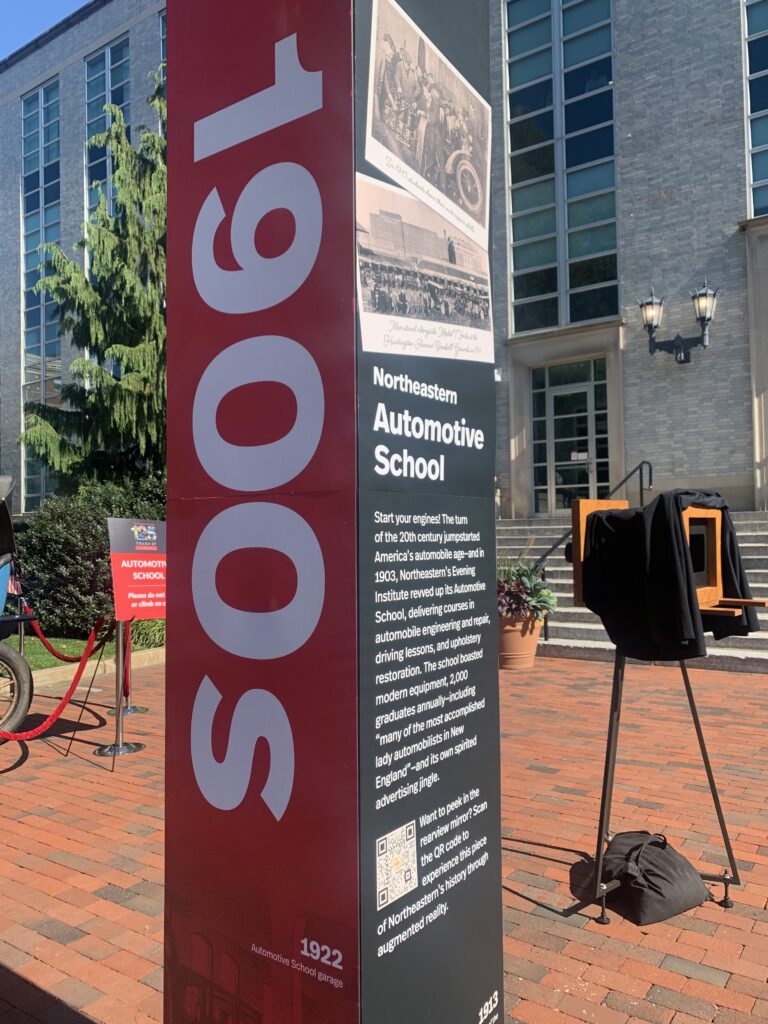

Since October, Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections processing assistants have been inventorying the records of Stull & Lee, a Boston-based architectural and urban design firm founded by Donald Stull in 1966. The firm is still active today, under the leadership of David Lee. The records held by Northeastern date from the 1960s to the early 2000s, spanning over 400 boxes and 700 tubes, and they document hundreds of projects, including the Southwest Corridor, Ruggles Station, and Roxbury Community College. Meet our processing assistants as they go through the collection, box by box.

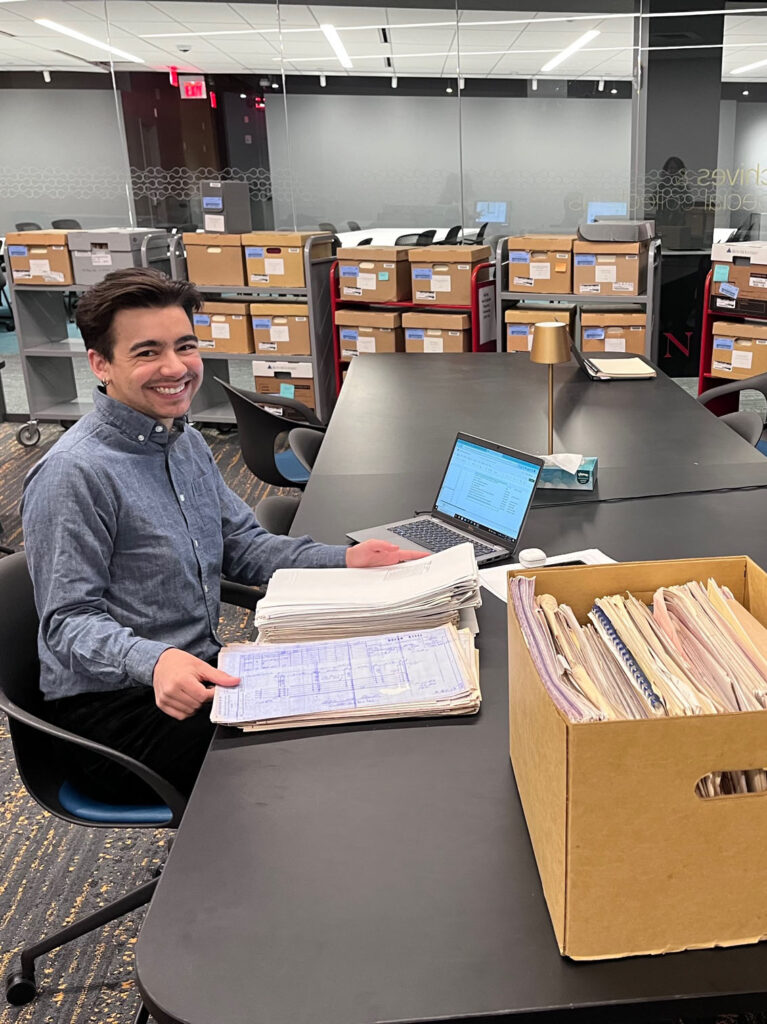

Samuel

I’m Samuel Edwards (he/him). I just completed my Master of Arts degree in Library and Information Science with a concentration in Archives Management at Simmons University, and I have a Bachelor of Arts in History and Playwriting from Hampshire College in western Massachusetts. Some of my interests in archives include the history of social movements, LGBTQ+ history, local history, and anti-racist archival work. Outside of my archival work, I enjoy creative writing, theater, and playing Dungeons & Dragons with my friends.

Working on the Stull & Lee records has been an enlightening experience. I didn’t have a lot of familiarity with architecture or architectural records prior to working on this collection, but it’s fascinating to realize how much goes into creating just one building. You don’t just have the architects, but also electricians, plumbers, and other trades that help create the building. I have a newfound appreciation for buildings that previously just blended into the background, especially the buildings I walk by daily on my way to Northeastern which were designed by Stull & Lee, such as Ruggles Station.

Julia

I’m Julia Lee (she/her). I recently graduated from Northeastern University with a Bachelor of Arts in English and Theatre, and my final co-op was as a digital assistant for the Massachusetts Archives. My archival interests include early American history, including the Revolutionary War, Asian-American history, and the history of Boston.

For me, working with the Stull & Lee records started with inventorying boxes of files belonging to several architects, including the firm’s namesakes Donald Stull and David Lee. It turns out that the two men had quite distinct organizational styles. While several of Lee’s folders included colorful titles patterned after the T’s Orange Line signs, Stull favored concise alphabetization for his files. I’ve enjoyed the greater understanding I’ve gained of Boston’s architecture, transit, and public works through working with the collection, especially about the area around Northeastern, where I’ve lived for over four years now. This is my second time working in an archive, and it has served to solidify my goal of obtaining a Master’s degree in Library and Information Science in the coming years.

Aleks

I’m Aleks Renerts (he/him). I am a current graduate student at Simmons University in the dual Master of Arts degree program in History and Library and Information Science, with a concentration in Archives Management. My academic background is in history, with a focus on the Hispanic world and histories of class, gender, and colonialism. I received my Bachelor of Arts in History from McGill University, and have since partially redirected my focus to archives and archival research.

Something I’ve found interesting in the Stull & Lee records is the massive degree of collaboration that every architectural project depends on. Memos, notes, letters, logs, and drawings are sent back and forth with revisions, showing the complex process that goes into completing a project. There’s an incredible level of detail for all the parts of a completed structure, from steel framing and floor tiles to the mechanics of a door lock. Working on Stull & Lee has given me an appreciation of just how much detailed work goes into every part of constructing a building.