Celebration, Activism, and Outreach in the Theater Offensive Records

While Pride is recognized as a protest, it can also be a time of celebration of the LGBTQIA+ community and queer identity. Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections is fortunate to steward the records of The Theater Offensive, a queer performing arts organization which is still alive and thriving in Boston today and will soon celebrate its 35th year of operation in 2024. Founded in 1989 by Abe Rybeck and other artists, the Theater Offensive strived to combine art and activism for the benefit of the LGBTQIA+ community throughout New England and, eventually, nationally.

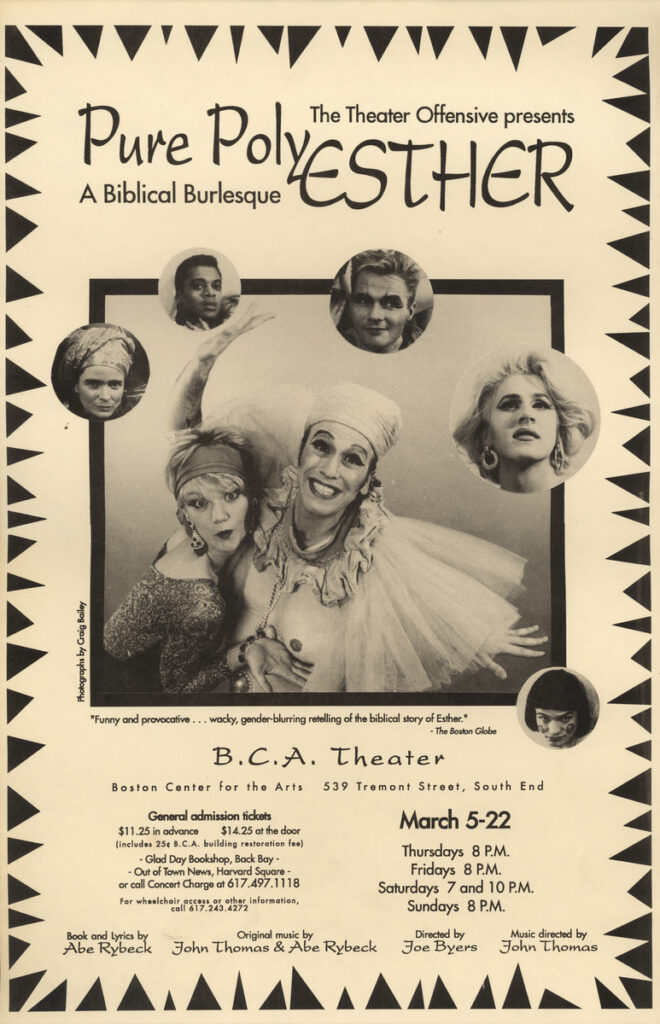

Since its founding, they have put on numerous performances, festivals, and community programs. Of note in Northeastern’s digital repository is the performance of Pure PolyEsther: A Biblical Burlesque, an adaptation of the story of Esther from the Old Testament as a part of Purim celebrations. Written by Rybeck, Pure PolyEsther was described as a “hot, flamboyant Mardi Gras…[that] melts the edge off the bitter New England winter.” It is an intersectional celebration of both Jewish and queer traditions.

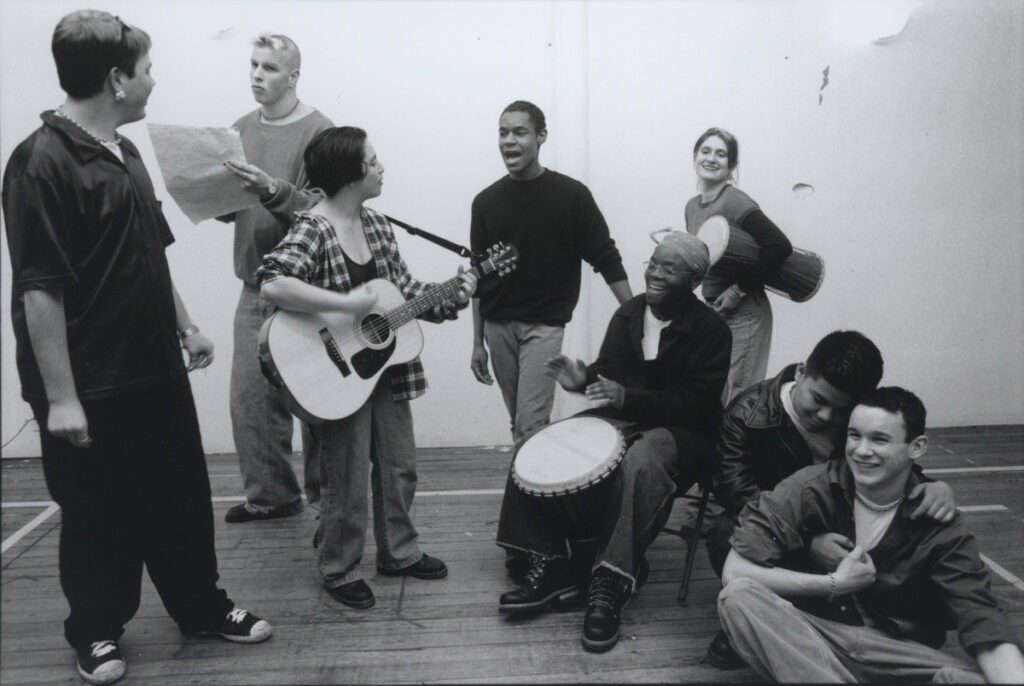

The Theater Offensive has also uplifted LGBTQIA+ youth with their True Colors program and their youth outreach performances. These have included the Living with AIDS Theater Project’s Lessons from the Heart, which educated teens on ways to combat the AIDS epidemic, highlighting an intergenerational conversation and relationship between queer youth and adults that remains incredibly valuable to this day.

The Theater Offensive continues to be an important cultural institution in Boston, and its records illustrate a rich and robust past that has championed queer creativity and community. To learn more about the Theater Offensive’s work not just this Pride Month but all year round, check out the resources available through the digital repository and University Archives and Special Collections!

Sources:

“History.” The Theater Offensive, https://thetheateroffensive.org/history.

“Pure PolyEsther.” The Theater Offensive records (M082). University Libraries Archives and Special Collections Department.

“‘Pure PolyEsther’ press release.” The Theater Offensive records (M082). University Libraries Archives and Special Collections Department.

The Theater Offensive records, M082. Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections. https://archivesspace.library.northeastern.edu/repositories/2/resources/856 Accessed June 23, 2023.

“True Colors Youth Theater, ‘Love + Mosquitos.’” The Theater Offensive records (M082). University Libraries Archives and Special Collections Department.