Bringing It All Together: Methods for Cataloging News Articles for the BNDA Version 2.0

Since its initial launch in September 2022, the Burnham-Nobles Digital Archive (BNDA) has established itself as one of the most comprehensive digital records of racial homicides collected to date. This blog series aims to highlight the work of the archivists on the BNDA team and their experiences preparing for the launch of BNDA Version 2.0. You can read more about the Version 2.0 update in Gathering the Red Record: A Two-Day Convening on Linking Racial Violence Archives.

Methods Overview

The first thing I have to say about the archival work methods for cataloging news articles at the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project’s BNDA is that they are a team effort. The workflow structure is maintained through shared instructions, templates, the data dictionary, and a responsive, organized supervising team.

All of the archives assistant work is digital. Archives assistants receive batches of news articles to catalog in the form of spreadsheets with links to images of the original newspaper articles stored in the Digital Repository Service. We then verify those articles against information we currently have and complete standardized fields for the information we want supplied. If we encounter a question about the records that we can’t answer with assurance, we flag it to be reviewed by either our supervisors or the legal team.

When completed, those standardized spreadsheets are reviewed by the supervising team and transformed into a format compatible for inclusion in the BNDA. Having multiple team members verify information improves the accuracy of the records and makes for sustainable collections processing practices.

Our goal is to add as much accurate and data-verified cataloged information as possible in order to provide supporting evidence of each incident, case, and victim identifier. These standardized identifiers, as well as authorized names for each unique individual, allow the team to take advantage of the relational-based search capability of the Airtable database. Not only does this system help us make better cataloged records, it allows for more retrievable information for future research.

Examples in the Records

Washington Sniper Victims

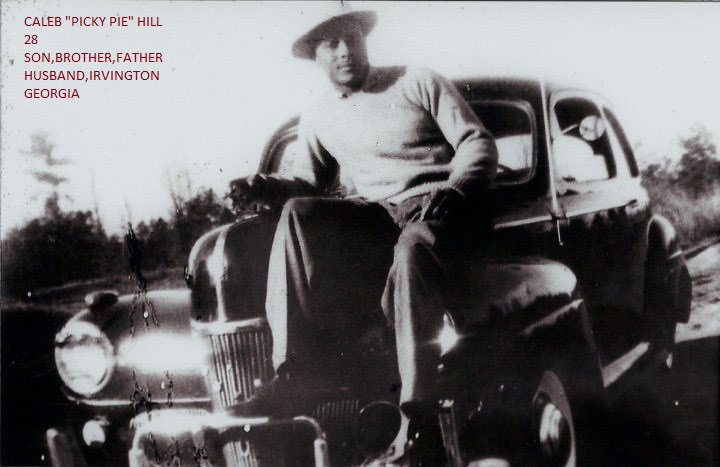

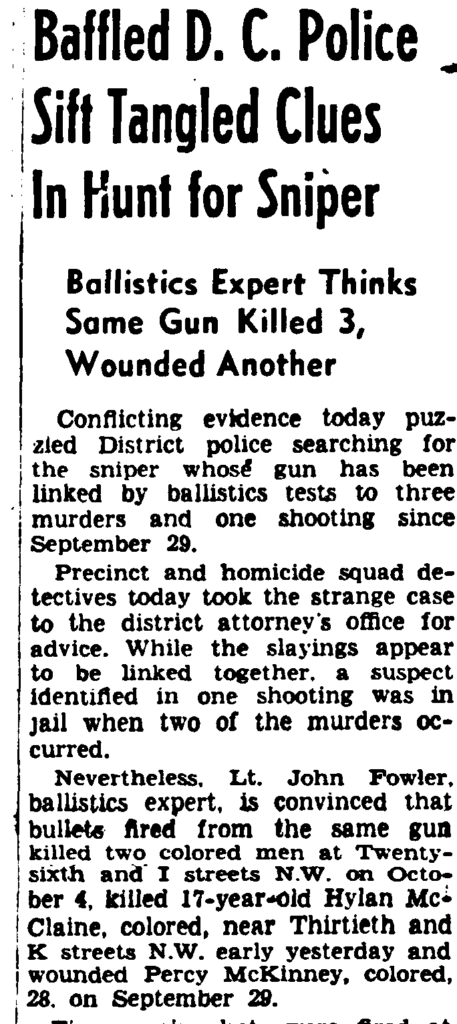

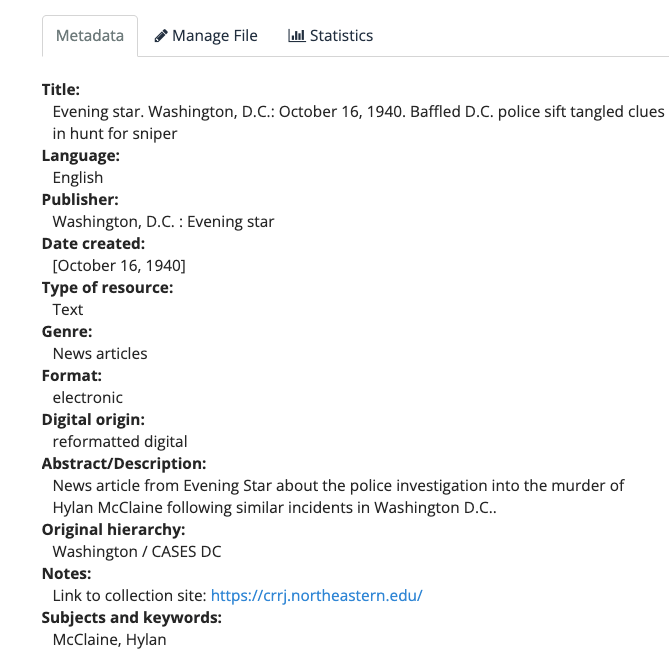

One example of data verification is to identify the victim(s) present in a news article whenever possible, even when minimal information is present. Breaking news articles often lack details. Names can be absent or incorrect, or focus on the perpetrator of the crime rather than the victim. One strategy I find helpful is to work by victim-subject, going through batches of news articles that are all related to one victim or group of victims. This allows me to glean patterns of context clues that allow for victim identification even if the victim is unnamed.

I found this strategy particularly helpful when working with a case related to a serial sniper who murdered multiple victims in Washington, D.C., in 1940. Three victims identified over the months of press coverage were Hylan McClaine, Lushion Sam Banks, and Theodore I. Goffney, but the chronological order of their murders was not shared. Press coverage of the sniper continued into the 1960s, long after the trial, with inconsistent reference to the victims. At the BNDA, we can link the victim names at the forefront of these articles in our catalog, centering the narrative around the victims rather than the perpetrator.

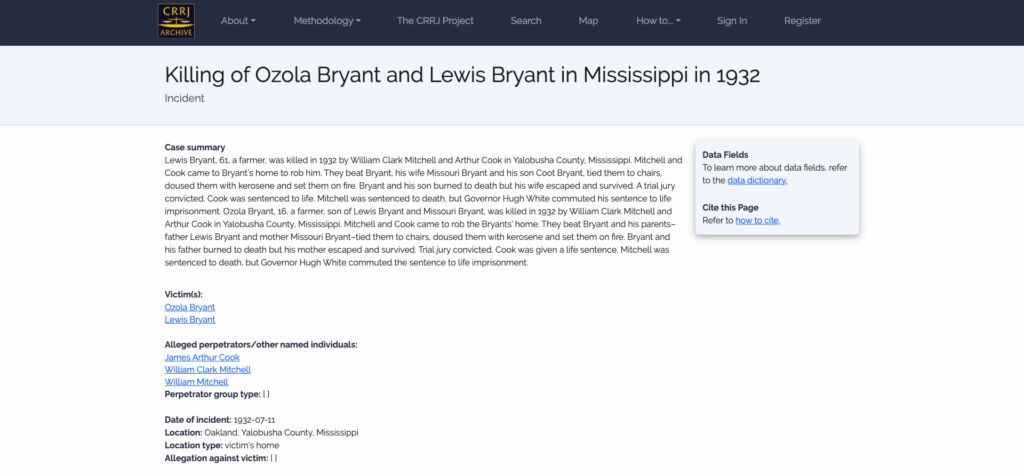

Bryant Family Murder

The research crucial work that aids in the cataloging effort is also on display in the case of the 1932 Bryant family murder. The news coverage of the tragic murder of the Bryant family was sometimes unclear about which family members survived and which were killed in the horrible robbery, torture, and death by arson. Some articles appeared sympathetic to the murderers and provided little to no details on the victims.

Our Airtable database supports a field for notes written by Project Historian Jay Driskell when they are available. Through Jay’s notes, I could confirm with certainty that the father and son, Lewis and Ozola Bryant, were murdered. The mother, Missouri Bryant, survived. The more detailed news articles corroborated these facts. The Bryant murder trial also stands out as a case that upheld the murder charges against a white killer despite appeals up to the Missouri State Supreme Court.

Given the graphic nature of the emotional events and the polarized reporting, I was grateful to have ready, retrievable access to previous work to clarify the Bryant family’s story in order to help me accurately represent the family in the cataloged work. I also benefitted from the concurrent work of another archives assistant and the support of my supervisor, Project Archivist Joy Zanghi.

These cases and many more are available in BNDA Version 2.0 and you can browse the current version now. I had the privilege of working with archival methods developed over the past 18 years of the project, taking into account the humanity of the sensitive subject matter. The final result is that the CRRJ developed an archival format with the BNDA that allows for the data within it to be scalable, buildable, and retrievable for the future.

CRRJ Archives Assistant Stephanie Bennett Rahmat (she/her/hers) has 17 years of experience working with historic and cultural heritage resources throughout the U.S. She completed her Master of Library and Information Science degree at Simmons University in 2021, with a focus on Archives Management and Cultural Heritage. She came to work in the archives and libraries after a career in North American archaeology.