A Dana Hall School Intern’s View of the Archives

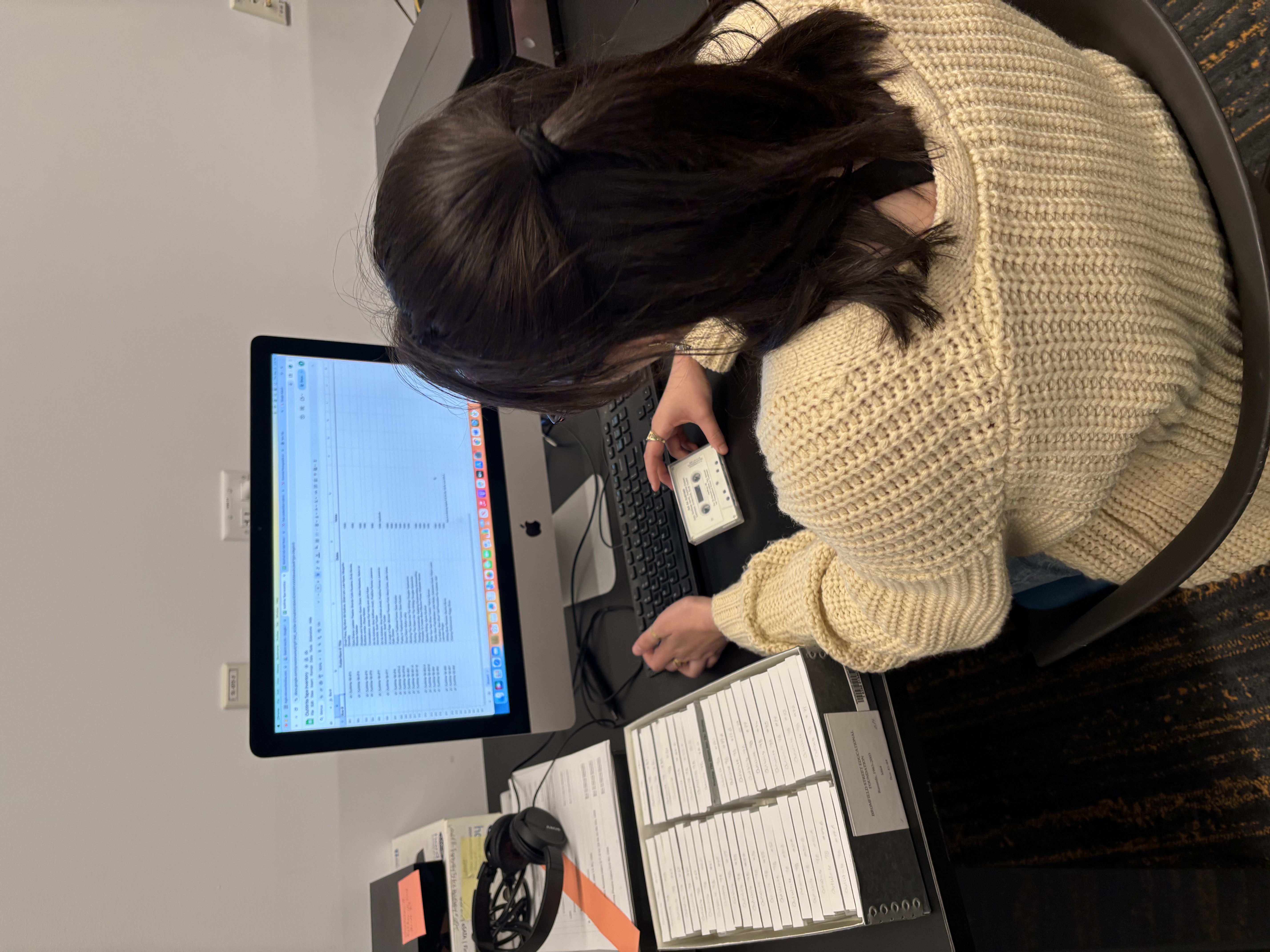

For the past two weeks, the Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections has had the pleasure of working with Ava Scharf, who is finishing her senior year at Dana Hall School and chose to do her senior internship at the local archive.

During her time with us, Ava has met with archives and library staff, shadowed meetings and reading room interactions, reorganized and tidied the Bromfield Street Educational Foundation’s Prison Newsletter collection after a semester of class uses, and inventoried tapes from the OutWrite conferences. After graduating from Dana Hall, Ava will join Northeastern as a first-year Husky this fall.

Before Ava heads off to enjoy her summer before her first year at Northeastern, she kindly agreed to answer some questions about her time working with us this May.

What surprised you about working in the archives?

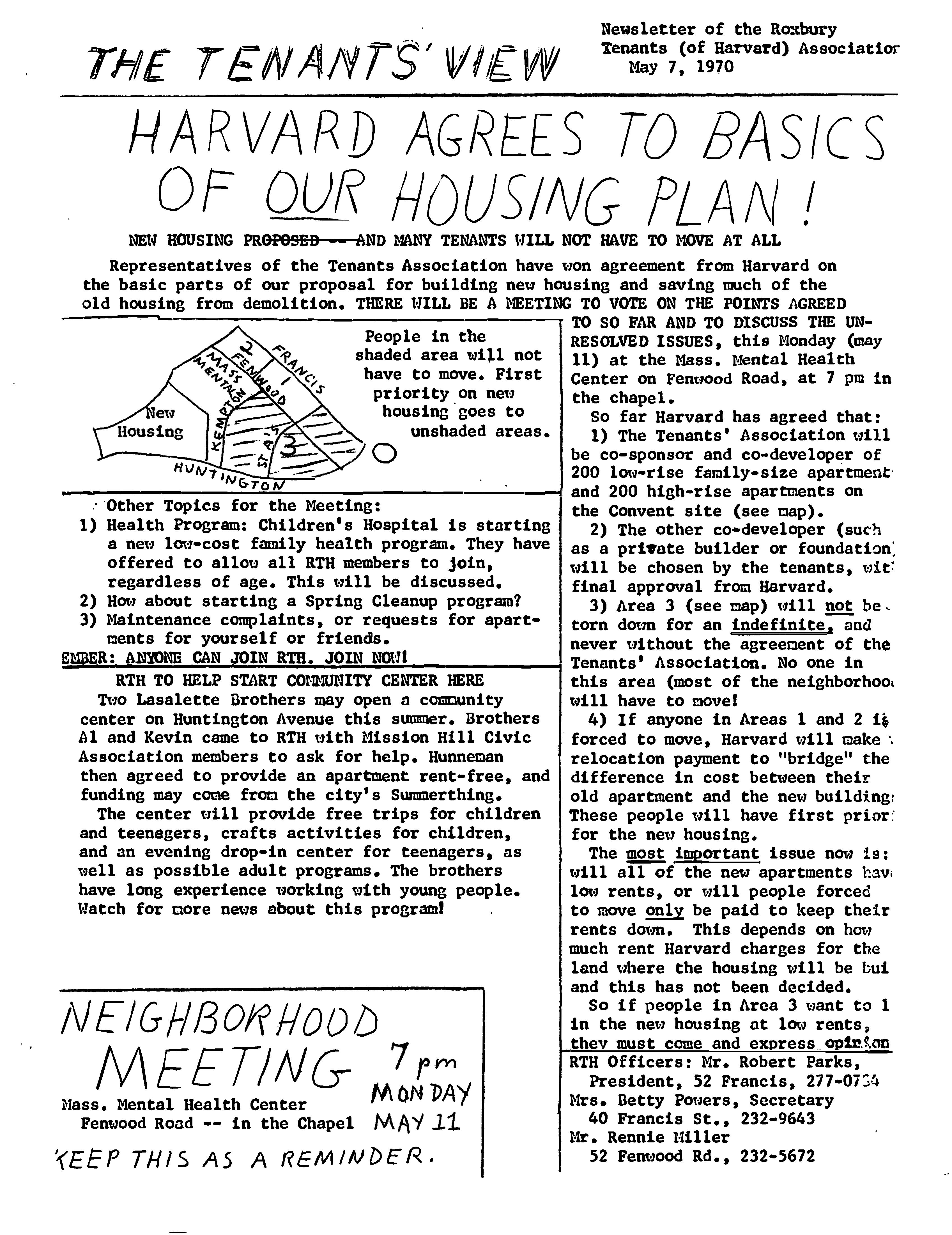

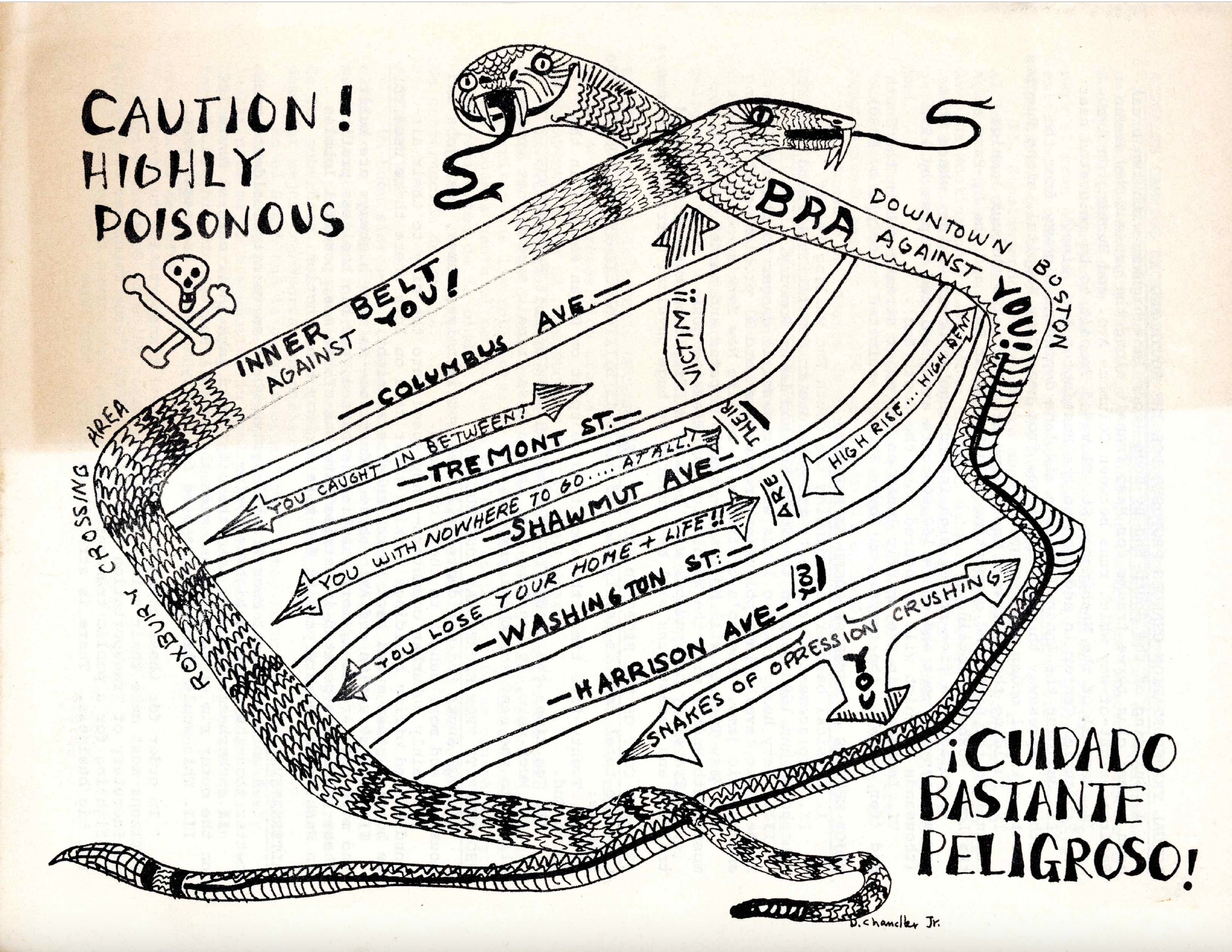

How much recent stuff there was. A lot of the stuff here was more recent. It was fun to see the newspaper and the handwritten papers from people who are still alive. I thought that in archives, there would be more books, but being able to see all the handwritten notes and papers that are loose portray more about everyday life than a book does. I felt humbled by trying to read some of the cursive.

What was an item/record in the collections that you liked seeing?

I really enjoyed seeing the Fenway Alliance records. I really thought I would like seeing the board meeting stuff, but I ended up liking seeing the everyday life sort of things. I liked seeing the art project adding door knobs to lampposts they planned.

I really enjoyed looking at the prison newsletters. I’ve never seen anything like that before. I really enjoyed getting my hands on something and seeing what was going on in prison at the time. I really like the Dragon Prayer Book — it was so small and so cute — and the artists’ books, especially the miniature ones.

Honestly, I really liked looking at everything here! Who wouldn’t want to look at mini art books?

How would you explain your time at the archives to family and friends?

A lot of online paperwork. It’s a lot of organizing. It’s kind of similar to being a library page at Dana Hall, which is nice. There’s a lot more specific jobs than I thought there were! Archivists are split into subcategories and there’s a lot of communication and talking between those subcategories that I didn’t know existed. At one level, it was what I expected: you have old papers, and I saw old papers! I would honestly say it is really a mix of history, reading, and organizational skills. And cursive…lots and lots of cursive.

Any advice for new first years (like yourself this fall) who want to use the archives?

Aimlessly wander through the archives’ papers. With the artists’ books, I was less terrified of breaking them after handling one. Getting experience early on and learning how to use the archives and booking an appointment and being here makes it much easier. If you come in and you research something for fun versus when you are stressed and writing a paper, it is going to be helpful. Venture down here at least once so you get a feel for things. And you can’t bring your drinks in here. No coffee! Also, start early: there are so many boxes to go through!