The following is a series written by archivists, academics, activists, and educators making available primary source material, providing pedagogical support, and furthering the understanding of Boston Public School’s Desegregation history.

This Q and A was reprinted from http://info.omeka.net/2016/03/site-highlight-stark-and-subtle-divisions/ with permission

Archivist, historian, educator, and baker of all things chocolate, Marilyn Morgan (@mare_morgan), investigates—and encourages students to explore—social trends, cultural stereotypes, and discrimination throughout American history. Her class site, Stark & Subtle Divisions: A Collaborative History of Segregation in Boston, showcases letters, photographs, legal documents, artifacts, and interviews that explore the federally-mandated desegregation of Boston public schools. Unearthing materials from various Boston-area archives, students selected a representative sampling and used Omeka.net to present them together in new collaborative context. The site runs on an Omeka.net Platinum plan

Archivist, historian, educator, and baker of all things chocolate, Marilyn Morgan (@mare_morgan), investigates—and encourages students to explore—social trends, cultural stereotypes, and discrimination throughout American history. Her class site, Stark & Subtle Divisions: A Collaborative History of Segregation in Boston, showcases letters, photographs, legal documents, artifacts, and interviews that explore the federally-mandated desegregation of Boston public schools. Unearthing materials from various Boston-area archives, students selected a representative sampling and used Omeka.net to present them together in new collaborative context. The site runs on an Omeka.net Platinum plan

1. Briefly explain how you came to the project.

Last year, I became the Director of the Archives Program (History MA) at UMass Boston and created a new course “Transforming Archives and History in a Digital Age.” My goals for this course involved having students: conduct primary research in local collections, select and scan materials, create metadata for digitized items, build a collaborative digital archive, develop subject-area expertise, and design an online exhibit. Because I teach history and archives, I focused the class on a historical topic—the desegregation of Boston Public Schools (BPS). Last year marked the 40th anniversary of the federally-mandated integration of BPS; various separate archives in the area hold collections that document that complex history.

As I was developing my course, Giordana Mecagni, Head of Archives and Special Collections at Northeastern University initiated a comprehensive cross-institutional scanning project to make archival materials related to the desegregation of BPS available in a large digital library. Boston Library Consortium funded the project that is supported by the technical infrastructure of the DPLA and Digital Commonwealth. This year, work my students are completing for their Omeka site—scanning and creating metadata for Boston City Archives—is feeding into the larger BLC initiative.

2. Why did you decide to build on Omeka.net, as opposed to a standalone Omeka site or some other platform?

Omeka provides a wonderful teaching tool for archivists and historians. It gives students hands-on experience implementing archival theory; it permits them to showcase historical research; and, ultimately, it enables them to create digital history for a public audience.

Before I created my course, I searched for platforms that would meet my teaching goals. I wanted students to learn technical skills and acquire hands-on experience implementing practices used by digital archivists. But I also wanted students to immerse themselves in scholarly historical research and to create engaging and educational exhibits for a general audience. There aren’t many platforms that allow one to accomplish all of that.

While other exhibit-building platforms exist, Omeka allows students to create a digital archive from start to finish. This entails selecting and scanning documents then creating metadata for digitized images. That back-end work teaches essential technical skills that aspiring archivists and digital historians need to hone. Equally important, when constructing Omeka exhibits, students must think critically about the items collectively and weave together narratives that form cohesive exhibits.

To be honest, circumstances beyond my control affected my decision to use Omeka.net instead of creating a standalone site. My university did not have the technical infrastructure to support the standalone Omeka site. With Omeka.net there’s no need to have IT support or server space. I was pleased to discover that Omeka.net doesn’t limit one’s creativity in building a site.

3. What piece of advice would you offer to someone planning to use Omeka.net with a class of graduate students?

Build in plenty of time to learn and experiment, don’t be afraid to take risks, collaborate, and don’t get discouraged!

When I decided to use Omeka.net in my course, I had absolutely zero experience using the platform. I confessed to my students in the first class that I had no idea if we’d be able to build the robust site we envisioned; but, even if we failed, we would have learned a great deal. I encouraged them not to obsess over individual grades and to approach this as a truly collaborative project—by the nature of the project, either we all succeeded or we all failed, to some degree.

Collaboration proved key to building a successful site in many ways. I’d advise anyone beginning to teach with Omeka to identify local resources—both people and collections at local archives or libraries—that you can incorporate into your site’s construction. When beginning this project, I blindly reached out to Marta Crilly, Archivist for Reference and Outreach at Boston City Archives—I knew they housed ample material related to our topic. Over the past year and a half, Marta and I developed a mutually beneficial collaboration. I reached out to librarians, archivists, an audio engineer, and even a copyright attorney, at local institutions; the input of each helped me to create a robust site.

4. How did using Omeka change your and/or your students’ thinking about the content?

Our project’s topic—de facto segregation and the federally-mandated desegregation of Boston Public Schools—provoked deep controversy in Boston. In the mid-1970s, the issue of desegregation provoked violent confrontations and pitted white neighborhood against black neighborhood. Over forty years later, the topic continues to ignite heated reactions locally.

Perhaps one of the biggest surprises was learning that the heated reactions to desegregation of Boston Public Schools reached far beyond Boston. Using Omeka’s map tool, students could demonstrate that individuals from around the nation and the globe watched the media report on this issue. In the sampling of letters students selected, they discussed letters sent from as far away as Mexico, Germany, and Australia.

Using Omeka, I realized quickly that creating an interactive digital exhibit on this controversial topic posed unique challenges that writing a traditional paper did not. If we proceeded incorrectly, instead of educating, we could provoke anger or alienate.

Many complex circumstances surrounded the intense reactions to desegregation including racism, class disparity, ethnic antagonism, political maneuverings, and contests for authority between local, state and federal agencies. As students dug into the archives and shaped exhibits in Omeka, we learned that race alone could not predict whether one supported or opposed desegregation of BPS. For instance, violent opposition to the decision to desegregate schools didn’t necessarily indicate opposition to school integration. Some citizens (black and white) championed school integration but vehemently protested the plan’s implementation—“forced busing” of their young children to schools far away from their neighborhoods.

Omeka helps us to convey the complexity of this emotionally-charged issue by showcasing the documents individually and allowing us to group them collectively to tell a narrative. In this way, exhibits can capture the raw fears, violence, and racist behaviors alongside of the hopefulness, compassion, and peaceful approaches.

5. What is one of your favorite items from the site to share (when talking about it)?

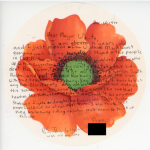

Letters written by third and sixth grade students to Mayor Kevin H. White constitute my favorite group of items. Some of the young letter-writers expressed fears while others boldly proposed no

nviolent solutions to school integration. While it’s difficult to pick one favorite, the letter below stands within my top three.

Writing on colorful stationary, the eleven-year-old student poignantly pleads that the mayor bus the teachers, not the students, “then maybe there wouldn’t be anymore stabbings and fights.”

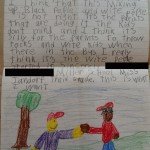

The letter below, written by a third-grade student, writes “this is what I want” above a crayon drawing of a white child and a black child shaking hands.

Omeka makes it possible to view the handwritten letters—complete with misspellings and mistakes—and freehand drawings that children used to convey sentiments more clearly than words. These personal details add immeasurably to the content of the letters. They also convey the extent to which concerns about desegregation of BPS permeated the physical and emotional well-being of many Boston’s residents—even children.

6. What is the benefit to using Omeka as a teaching tool?

Traditional research papers function as a dialogue between student and professor; creating a project in Omeka expands the discourse and fosters a collaborative working environment. The tasks of learning new technology, conducting historical research, applying archival theory, acquiring subject-area expertise, clearing permissions, and presenting findings in a public forum can be overwhelming when undertaken by one individual. As a result, when using Omeka, students quickly learn to actively collaborate with one another, sharing discoveries that might benefit a classmate’s exhibit or teaching technical tips. I’m so pleased that my decision to teach with Omeka allows graduate students to simultaneously learn new skills, apply theory to practice, and contribute to public education in a practical way.