Boston Campus Screen of “Dukakis: Recipe for Democracy”

Michael Dukakis is not only the former governor of Massachusetts, but he is also a well-known and beloved professor emeritus of political science in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities. In 2024, he became the subject of the documentary Dukakis: Recipe for Democracy.

Northeastern University will be hosting a screening on Tuesday, March 11.

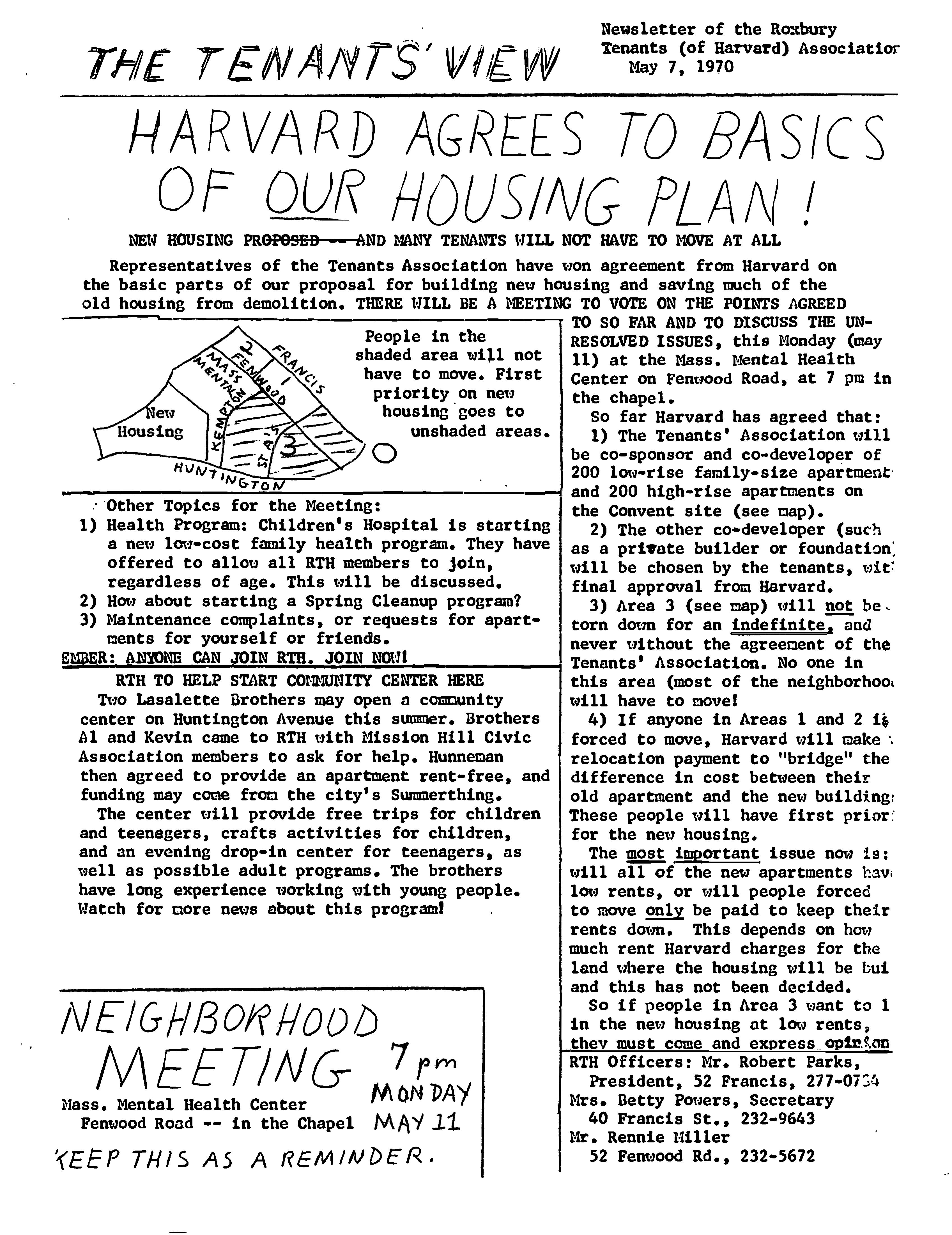

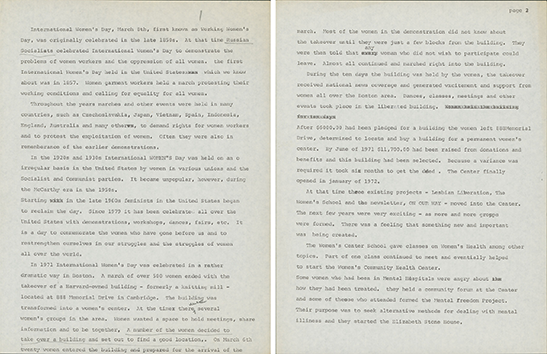

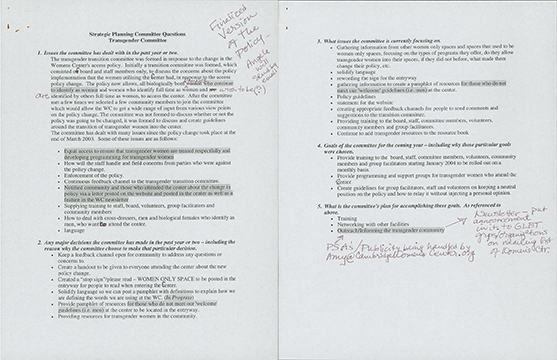

The Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections (NUASC) had the pleasure of providing archival resources for the film. The documentary features selections from Michael Dukakis’ Presidential Campaign records held at NUASC. The Dukakis collection spans from administrative campaign records to memorabilia like bumper stickers. Archives staff parsed through the collection’s correspondence on the hunt for information about the use of Neil Diamond’s “America” as the Dukakis campaign song and photos of Dukakis from his schoolboy days in Brookline.

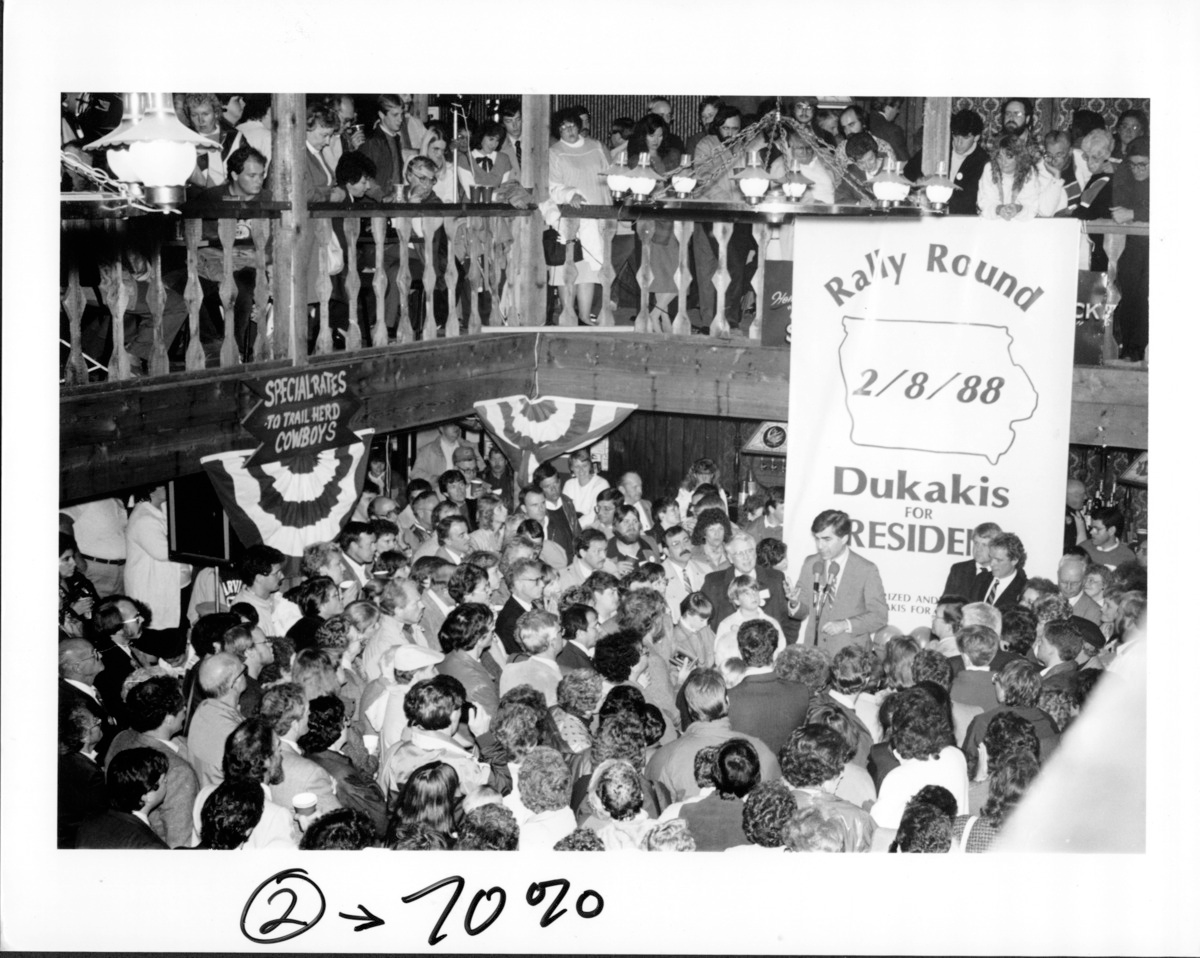

Final selections for use in the documentary include a photo of Dukakis and his wife Kitty on the back of a train called “The Duke Express,” and a photo of a rally in support of Dukakis’ presidential bid. Though these photos portray Dukakis with the essence of celebrity, the letters in the collection reflect an approachability that remains today, as evidenced in the film. The correspondence files are filled with letters from constituents and citizens outside of Massachusetts, wishing Dukakis good luck, bringing up issues they want to know about, and asking him to visit their hometowns.

The film premiered in October 2024 at the Coolidge Corner Theater in Dukakis’ hometown of Brookline.

The Northeastern University campus screening will take place on Tuesday, March 11, at 5 p.m., in the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs (310 Renaissance Park). Those interested in attending can register for the event with their Northeastern email ahead of time. Other screenings are listed on the film’s website.

If you’re interested in learning more about Michael Dukakis’ presidential campaign, the collection has been partially digitized and added to the Digital Repository Service. You can also contact the NUASC at archives@northeastern.edu to schedule an appointment or consultation.