Tastemakers Archives Provides a Glimpse into Music Format History

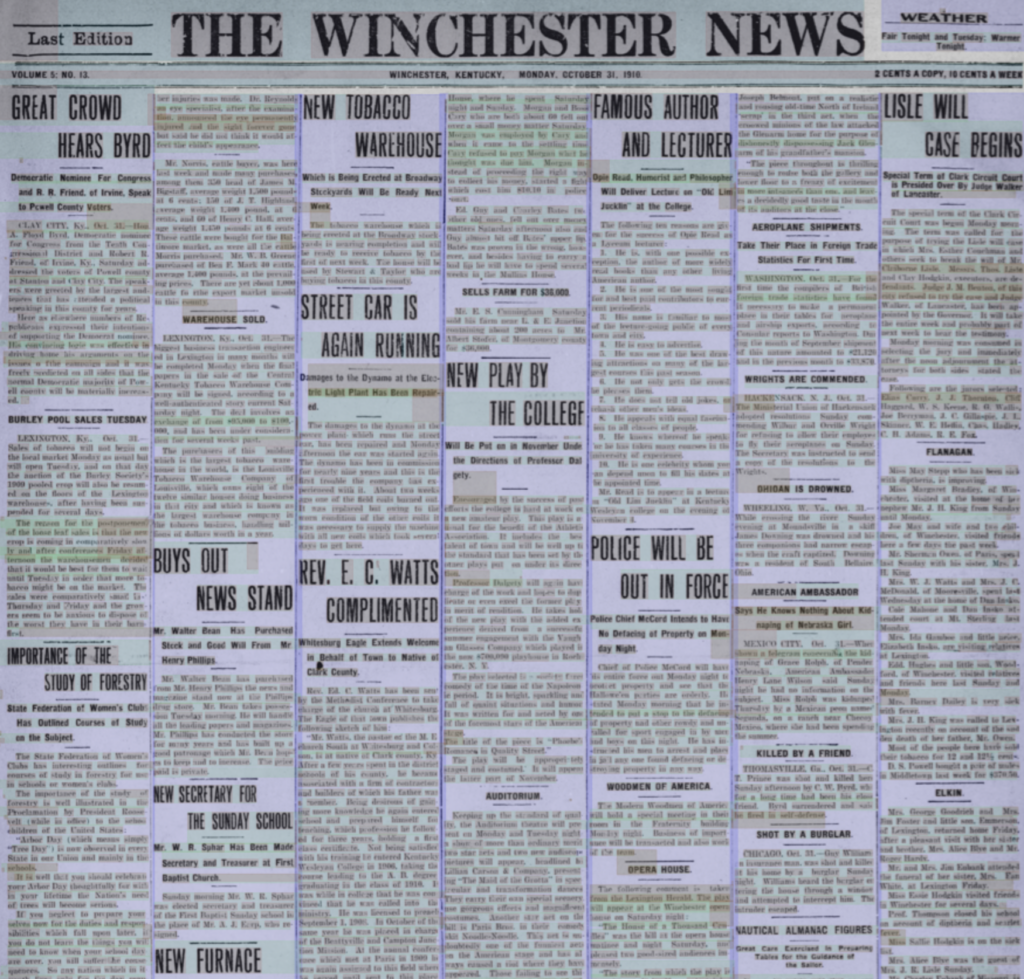

One of my recent projects was to digitize the very first issues of Tastemakers, Northeastern’s student-run music magazine, which began in 2007 and is still running today. Since the 2010-11 academic year, all issues were created in a born-digital format, so they were easy to add to the Digital Repository Service earlier this year. However, the first 19 issues were not, so it was my job to scan them on our Bookeye scanner and turn them into PDFs ready to be made accessible.

Since the issues in question date from 2007 to mid-2010, they fall exactly in the transitional moment of the music industry when legal streaming was still a novel concept, but CDs had fallen largely out of fashion in favor of iPods and other portable mp3 players. Consequently, as I was going through the magazines, I found an assortment of pieces that are retrospectively funny because we, in 2024, know the outcomes of all their speculations (most of which didn’t happen).

The articles I found fell into two broad categories: devices and streaming, both of which provide an interesting (as well as amusing) look at the future we imagined music would have at that time.

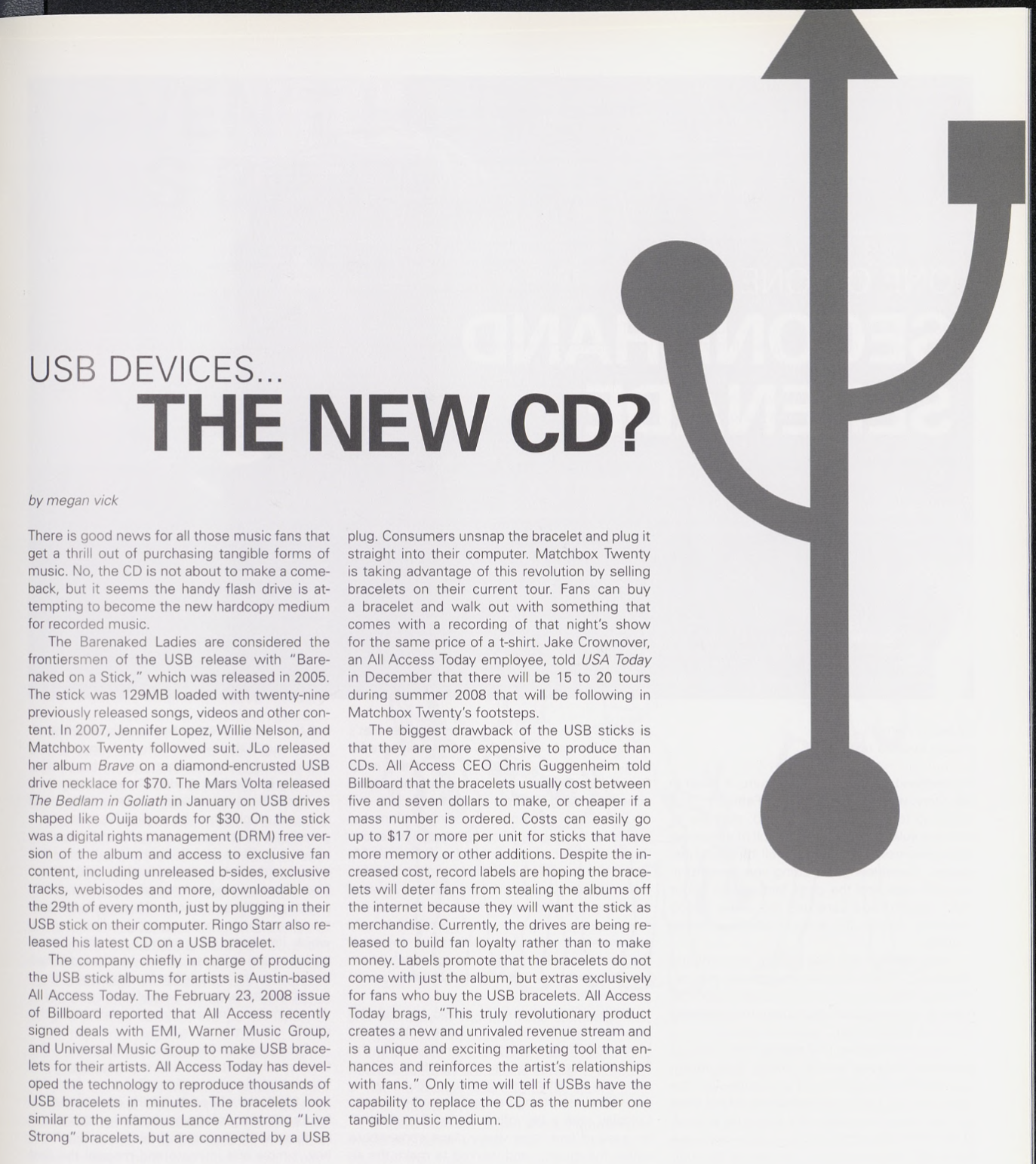

Let’s start with devices. The two pieces I found are on the potentiality of USB sticks and microSD cards as the dominant form of physical media to replace CDs. The USB article discusses a few bands and artists circa 2008, including Matchbox Twenty and Jennifer Lopez, who released albums on USB sticks embedded in rubber bracelets, primarily as a marketing gimmick. The author wonders whether if the technology will catch on in earnest or remain a ploy. At the time, vinyl was already starting to make a resurgence as the go-to medium for people who want their music on a physical object, and that group is comprised primarily of people who care deeply about the auditory and visual technical details of their music. So, I think the bracelets were never really going to work, since a group of mp3 files on a rubber bracelet couldn’t match up to either the quality or experience of vinyl on a record player, and thus eliminated their theoretical primary market. (It’s also funny to imagine collectors’ storage for a bunch of rubber bracelets. Would you keep them in a basket? Individual cases? One of those divider boxes for sorting hardware? On a pegboard on your wall?)

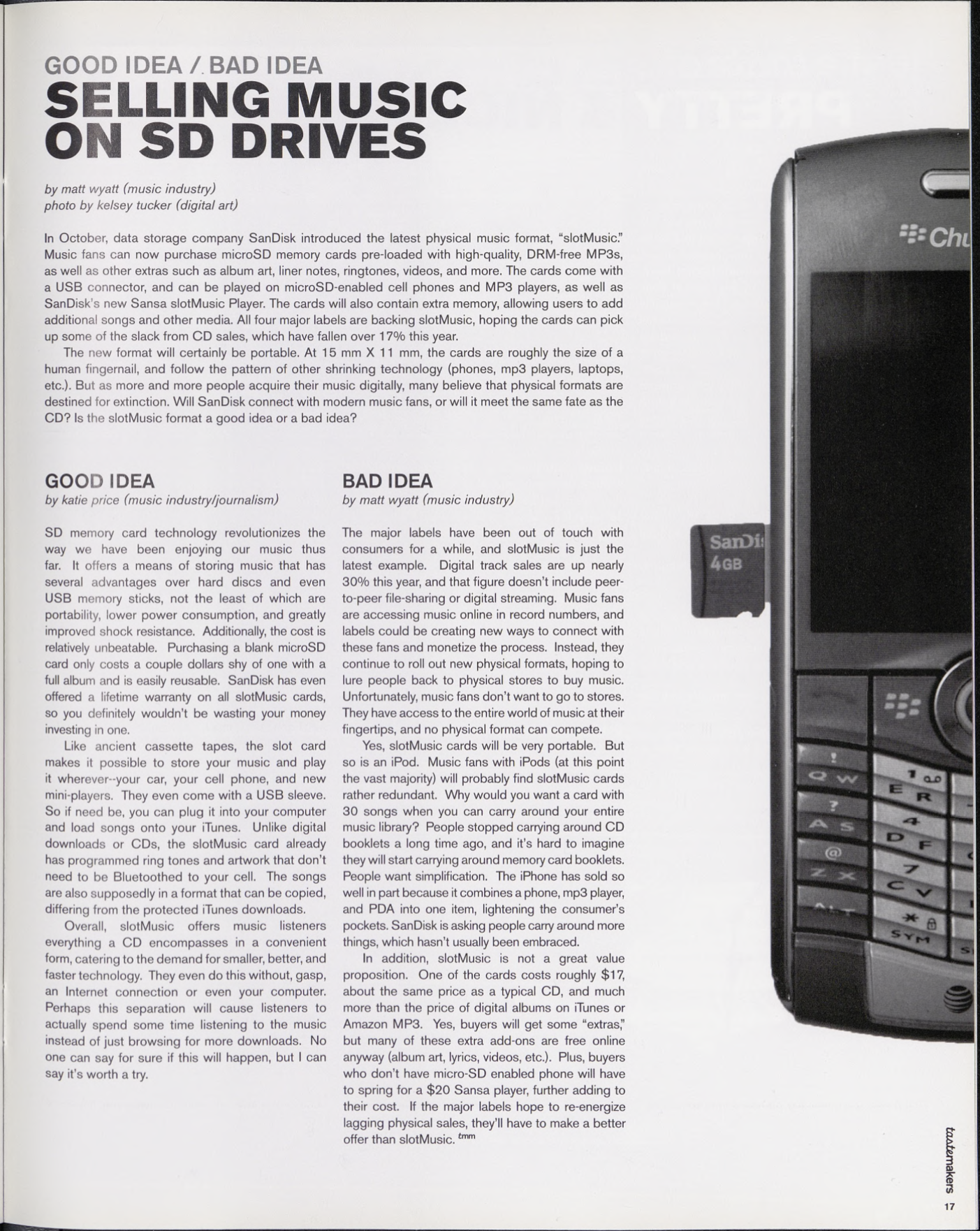

Meanwhile, the microSD card piece talks about an attempt in late 2008 by major record labels to supplant (or at least supplement) CDs with pre-loaded microSD cards, branding as slotMusic, that can go into any phone or mp3 player with a corresponding card slot. This one is interesting because it could have possibly been successful, but only in a universe where Apple wasn’t already the dominant force in the portable music player market. iPods were well established as everyone’s favorite internet-based mp3 player, and the iPhone was already becoming the most popular phone, which combined the two via a built-in iTunes app and completely removed the need to even have a separate device for music. Even if they had managed to carve out a market around Apple, rapid increases in storage capacity would have also rendered them useless within a handful of years. While 1GB was a significant amount of storage for the size of a microSD in 2008, 128GB microSDs were introduced in 2014, which is a 127,000% increase in about five years. They didn’t stop there. Today, microSD cards are available in sizes up to 1TB, which is big enough to fit 1,000 slotMusic cards on a single item. So, slotMusic never really stood a chance.

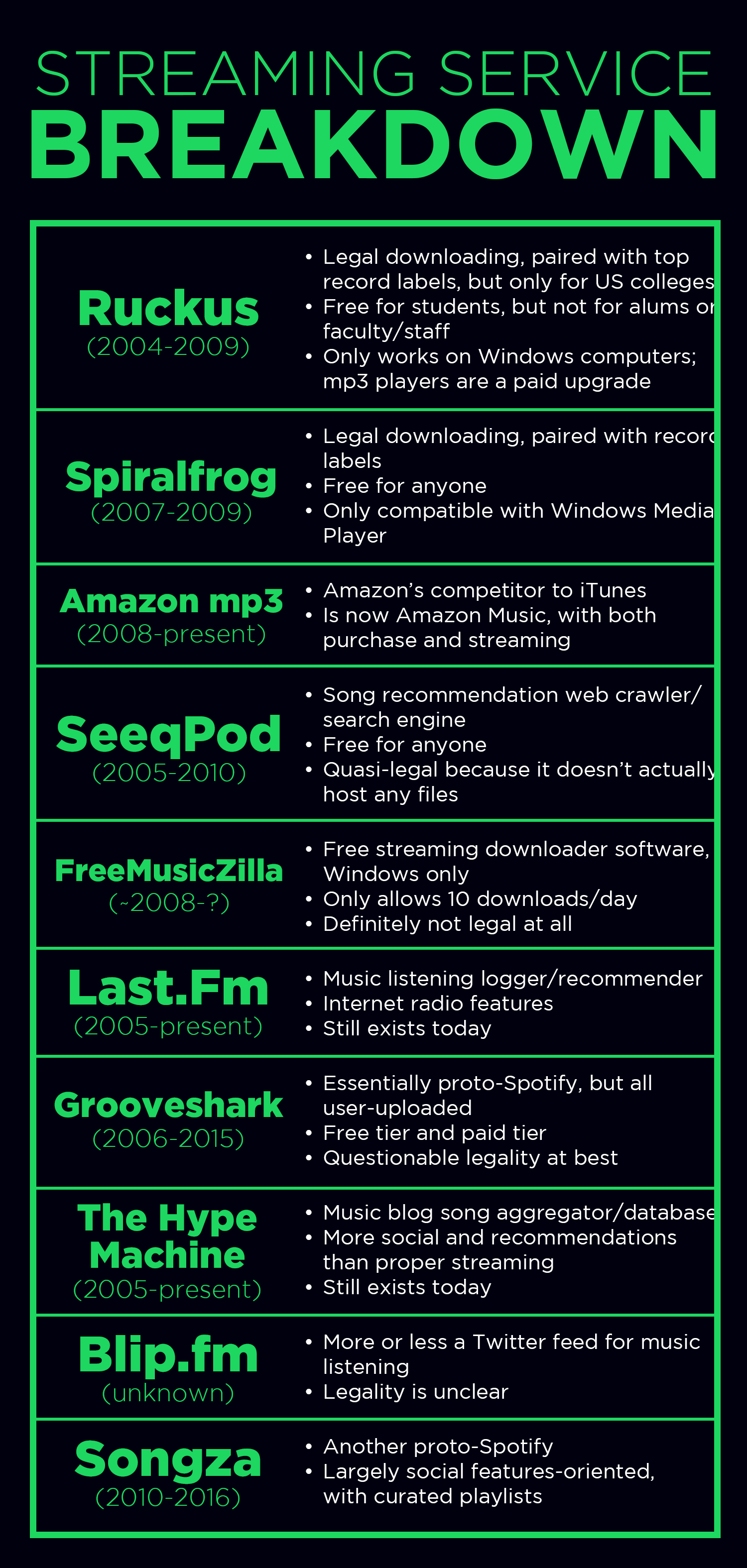

Now, on to streaming. Over the course of three years, Tastemakers published five different pieces about then-current and upcoming streaming services, effectively culminating (though not knowingly at the time) in a piece about the European launch of Spotify. Nearly all of the platforms mentioned are now entirely defunct, with some exceptions including Spotify and Amazon mp3 (now Amazon Music). The other remaining platforms now provide internet radio and recommendation sites, rather than streaming music, a fact that does not seem coincidental. Here’s a breakdown:

It’s also amusing now to think of Spotify as the hip new platform from Europe. Their article quotes other American journalists who had received early-access press accounts describing Spotify as “the world’s biggest iTunes collection” and “an almost infinite jukebox.” It sounds quaint in today’s world, but then you can’t describe something with words that don’t yet exist. Reading their predictions from 2009 about whether Spotify will be successful while others failed is like listening to someone try to predict the ending of a TV show that you’ve already finished.

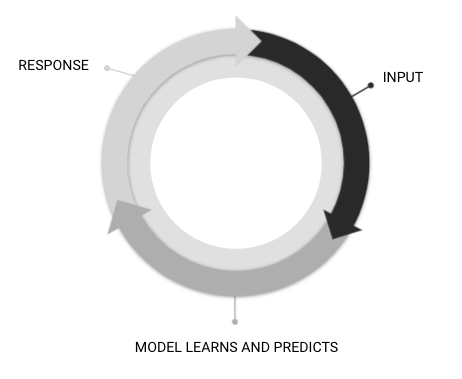

I sat for about 30 minutes trying to think of something to speculate for the future the way that these articles speculated about streaming. The conclusion I came to is that I don’t think there are any more technological advancements that music needs to make; you can get a device that fits in your pocket with up to 1TB of space and provides access to anything on Spotify, iTunes, and YouTube. Either that, or, like the writes of Tastemakers in 2007-2010, I cannot even conceive of what is yet to come, exactly because it has not come yet.