Boston Globe Archival Advisory: Highlighting the Dairy Festival

This blog post is the first in a series by members of the Northeastern University Library’s Digital Production Services and Archives and Special Collections teams sharing their favorite images and their role in the Boston Globe Library Collection digitization project.

My name is Kim Kennedy and I’m the Digital Production Librarian in the Northeastern University Library. In our recent push to digitize Boston photographs from the Boston Globe Library photo morgue, I coordinated the work with our vendor Picturae. In four months, they digitized 59 boxes of material. I developed a workflow to perform quality control checks on the digitized items and helped prepare them for upload to our Digital Repository. Most of these images are limited to the Northeastern community while we determine the rights status of the photographs, but a subset has been reviewed and is available to the public.

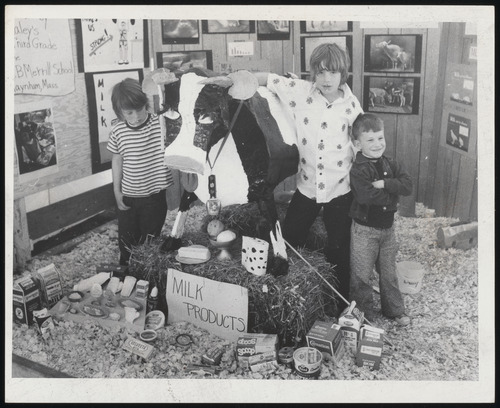

Some of my favorite images are of the Boston Common Dairy Festival, an annual event in which cows returned to the Boston Common (in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Common was used as a cow pasture by colonists).

Here are some resources to learn more about the Boston Common Dairy Festival:

Boston’s Uncommon Park; Common and Garden Provide Togetherness in 75-Acre Refuge, September 27, 1964, New York Times

An Uncommon Common, August 28. 1994, Boston Globe

The Singing Cowsills to Sing Out for “Cowes” During Boston Common Dairy Festival, June 1969, Vermont Farm Bureau News