Interlibrary Loan: Powering access to resources from around the globe

Announcing the Archives and Special Collections new portal to Boston’s latino/a history, http://latinohistory.library.northeastern.edu/!

Boston’s Latino/a Community History Collection contains images, documents, and posters selected from the Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción records and the La Alianza Hispana records held in the Northeastern University Libraries, Archives and Special Collections Department. The documents scanned from the collection include organizational charts and histories, committee and taskforce meeting minutes, fact sheets, by-laws, articles of incorporation, annual reports, program descriptions and brochures, newsletters, and organizational reports. The records available in this online collection document public policy formation, community relations, affordable housing, urban planning and housing rehabilitation, cultural and educational programming, violence prevention, and minority rights during the last decades of the 20th century.

The collection was originally scanned and made available in 2009 by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services but has since been completely overhauled. Each item was given additional item-level metadata allowing users to dig deeper into the collection. The searching and browsing interfaces were rebuilt using the Library’s Digital Scholarship Group’s CERES: Exhibit Toolkit, giving users immediate and searchable access to the collection. CERES is a user-friendly platform with which faculty, staff, and student scholars at Northeastern University are building WordPress exhibits incorporating curated digital objects.

To learn more about the Digital Scholarship Group and CERES, go to http://dsg.neu.edu/the-drs-project-toolkit-is-now-ceres-exhibit-toolkit/

[1] Dumanoski, Dianne. “Charlestown – ‘My Town” – Braces for Busing.” The Boston Phoenix, September 02, 1975.

Archivist, historian, educator, and baker of all things chocolate, Marilyn Morgan (@mare_morgan), investigates—and encourages students to explore—social trends, cultural stereotypes, and discrimination throughout American history. Her class site, Stark & Subtle Divisions: A Collaborative History of Segregation in Boston, showcases letters, photographs, legal documents, artifacts, and interviews that explore the federally-mandated desegregation of Boston public schools. Unearthing materials from various Boston-area archives, students selected a representative sampling and used Omeka.net to present them together in new collaborative context. The site runs on an Omeka.net Platinum plan

Archivist, historian, educator, and baker of all things chocolate, Marilyn Morgan (@mare_morgan), investigates—and encourages students to explore—social trends, cultural stereotypes, and discrimination throughout American history. Her class site, Stark & Subtle Divisions: A Collaborative History of Segregation in Boston, showcases letters, photographs, legal documents, artifacts, and interviews that explore the federally-mandated desegregation of Boston public schools. Unearthing materials from various Boston-area archives, students selected a representative sampling and used Omeka.net to present them together in new collaborative context. The site runs on an Omeka.net Platinum plan

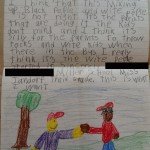

The letter below, written by a third-grade student, writes “this is what I want” above a crayon drawing of a white child and a black child shaking hands.

The letter below, written by a third-grade student, writes “this is what I want” above a crayon drawing of a white child and a black child shaking hands.

Omeka makes it possible to view the handwritten letters—complete with misspellings and mistakes—and freehand drawings that children used to convey sentiments more clearly than words. These personal details add immeasurably to the content of the letters. They also convey the extent to which concerns about desegregation of BPS permeated the physical and emotional well-being of many Boston’s residents—even children.

Omeka makes it possible to view the handwritten letters—complete with misspellings and mistakes—and freehand drawings that children used to convey sentiments more clearly than words. These personal details add immeasurably to the content of the letters. They also convey the extent to which concerns about desegregation of BPS permeated the physical and emotional well-being of many Boston’s residents—even children.

Project Overview

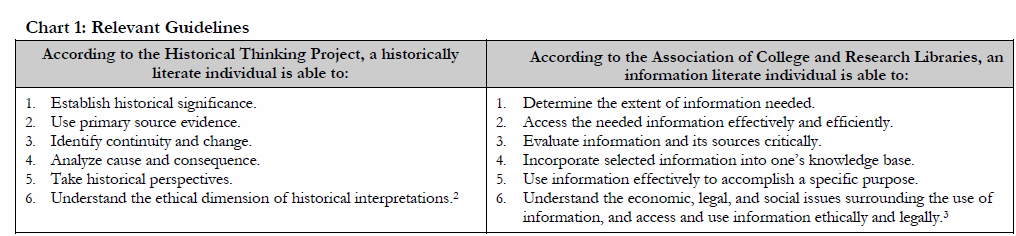

Suffolk University faculty, archivists, and librarians formed a collaborative team in 2015 to develop and disseminate open educational resources (OERS) based on the research collections held by Suffolk University. Archivists and librarians provided reference assistance, bibliographic instruction, research guides, technological support, and digitization services. The curricula were designed to develop students’ information literacy skills and allow them to take advantage of – and navigate the challenges of — a complex and sometimes overwhelming information landscape. In the next phase of the project, the team will develop and test additional OERs, evaluate the effects of student and faculty engagement with OERs, and create guidelines and recommendations for further OER use, expansion, and development at Suffolk and beyond.

Sample OERS (Open Educational Resources)

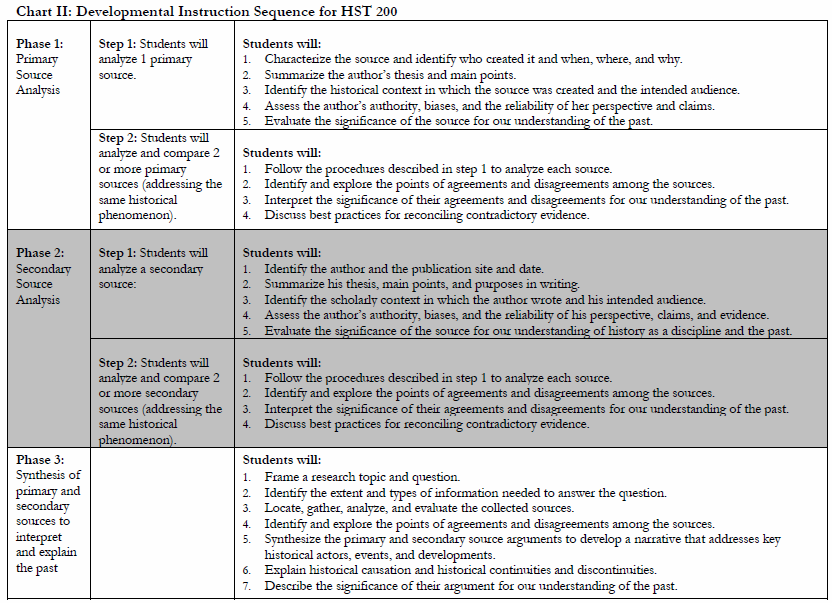

Using historical documents from Congressman Joe Moakley’s papers related to court-ordered busing in Boston, Professor Reeve created a variety of assignments and classroom exercises for her undergraduate history methods course, “Gateway to the Past: The Historian’s Practice.” Supplemented by lectures, readings, and discussion, Reeve used the assignments sequentially to ensure that students mastered historical thinking skills and then directly applied them to a capstone project. (See the course’s developmental sequence chart below.)

Project Overview

Suffolk University faculty, archivists, and librarians formed a collaborative team in 2015 to develop and disseminate open educational resources (OERS) based on the research collections held by Suffolk University. Archivists and librarians provided reference assistance, bibliographic instruction, research guides, technological support, and digitization services. The curricula were designed to develop students’ information literacy skills and allow them to take advantage of – and navigate the challenges of — a complex and sometimes overwhelming information landscape. In the next phase of the project, the team will develop and test additional OERs, evaluate the effects of student and faculty engagement with OERs, and create guidelines and recommendations for further OER use, expansion, and development at Suffolk and beyond.

Sample OERS (Open Educational Resources)

Using historical documents from Congressman Joe Moakley’s papers related to court-ordered busing in Boston, Professor Reeve created a variety of assignments and classroom exercises for her undergraduate history methods course, “Gateway to the Past: The Historian’s Practice.” Supplemented by lectures, readings, and discussion, Reeve used the assignments sequentially to ensure that students mastered historical thinking skills and then directly applied them to a capstone project. (See the course’s developmental sequence chart below.)

–This post was written by Professor Pat Reeve, History Department and Julia Howington, Director, Moakley Archive and Institute, Suffolk University, http://moakleyarchive.omeka.net/hst200

[1] Historical Thinking Project. http://historicalthinking.ca/historical-thinking-concepts. Accessed December 31, 2014.

[2] Association of College and Research Libraries, “Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education.” (May 26, 2015) http://www.ala.org/ acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency. Accessed March 1, 2016.

–This post was written by Professor Pat Reeve, History Department and Julia Howington, Director, Moakley Archive and Institute, Suffolk University, http://moakleyarchive.omeka.net/hst200

[1] Historical Thinking Project. http://historicalthinking.ca/historical-thinking-concepts. Accessed December 31, 2014.

[2] Association of College and Research Libraries, “Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education.” (May 26, 2015) http://www.ala.org/ acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency. Accessed March 1, 2016.